If history has taught us anything, it is that every great empire had its own weakness. For the Roman Empire, it was their vast frontiers that they struggled to protect, and for the Mongolian Empire, it was their unfamiliarity with maritime warfare.

Today, modern superpowers also have weaknesses, and for China, it is the Malacca Strait — the narrow stretch of water that connects the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean.

This narrow chokepoint is crucial for China's energy imports and trade, as a significant portion of its oil and goods transit through it. According to the Institute of Supply Chain Management's data, approximately 80% of China’s imported oil passes through the strait. Any disruption or blockade of the Malacca Strait could severely cripple China's economy and energy security. In fact, the Chinese have been aware of this weakness for decades.

In 2003, then-Chinese President Hu Jintao famously coined the term "Malacca Dilemma”, highlighting China's acute awareness of this strategic vulnerability. Since then, China has been on a relentless quest to eliminate this weakness, investing heavily in a multi-pronged strategy to diversify its energy supply routes and reduce its reliance on the strait.

Interestingly, China seems to have found that solution in trains.

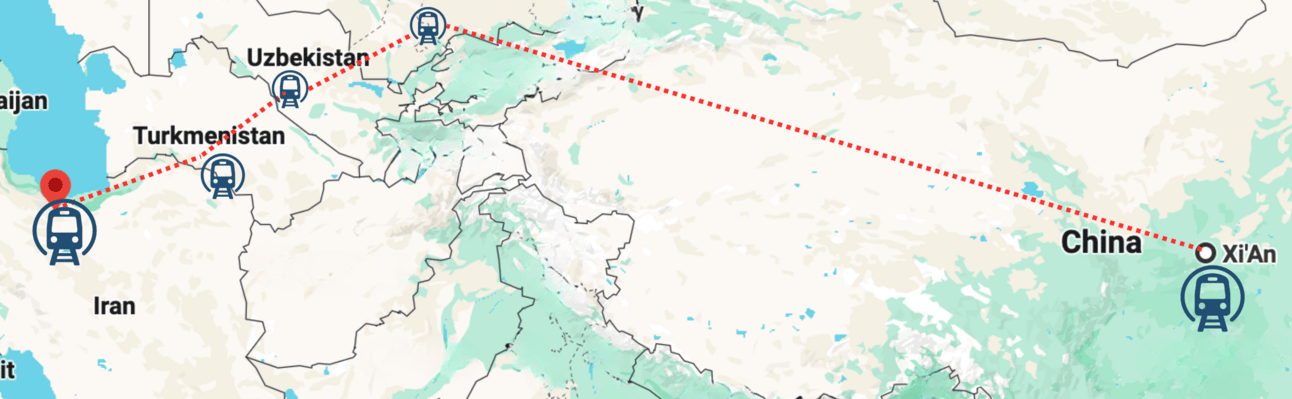

A freight train arrived at Tehran’s Aprin Dry Port on May 25, 2025. This was not any ordinary train. It was the first direct freight train linking Xi'an in central China to Tehran in Iran, traversing over 10,000 kilometers across Central Asia as part of the ambitious project to revive the ancient Silk Road.

This achievement is a significant event in the global trade landscape for several reasons. Firstly, it has successfully bypassed traditional maritime routes, offering a more direct and potentially faster alternative route.

Secondly, it has proven the viability of a land-based corridor. More importantly, the passage is sanction-free and beyond Washington's reach and Western influence.

In this issue of CrossDock, we’re breaking down the China–Iran rail link, its trade implications, and why it’s shaking up the global supply and finance order. Before we discuss the China-Iran rail link, it’s essential to understand the trade relationship between the two countries over the years. So, let’s begin there.

Band of Brothers

For years, China and Iran shared a relatively quiet economic relationship. It’s worth noting that, since 2005, Chinese investments in Iran averaged just $1.8 billion annually, far below what China poured into regional players like Saudi Arabia or the UAE.

But groundwork for something deeper was being laid.

Beijing had long been seeking a foothold in the Middle East, a region where the United States exerted significant influence. In that region, China wanted a partner willing to offer both economic access and political leverage.

Enter, Iran. Isolated by the West and under heavy US sanctions, Iran was open to the idea. What made it even more attractive was its geography: Iran sits at the crossroads of land and sea routes linking Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. That’s exactly the kind of hub China needs to bring its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to life.

And the interest was mutual. Iran has tried for decades to reduce its dependence on the West and escape the watchful eyes of the United States. In a 2018 speech, Iranian Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei laid it out plainly: “We should prefer the East to the West, and neighbors to distant countries.” That same year, Iran formally signed and became a part of China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Today, trade between China and Iran has expanded dramatically. In 2024, China solidified its position as Iran's major crude oil customer. It purchased 77% of Iran's crude oil exports, worth roughly $29 billion, according to data from analytics firm Kpler.

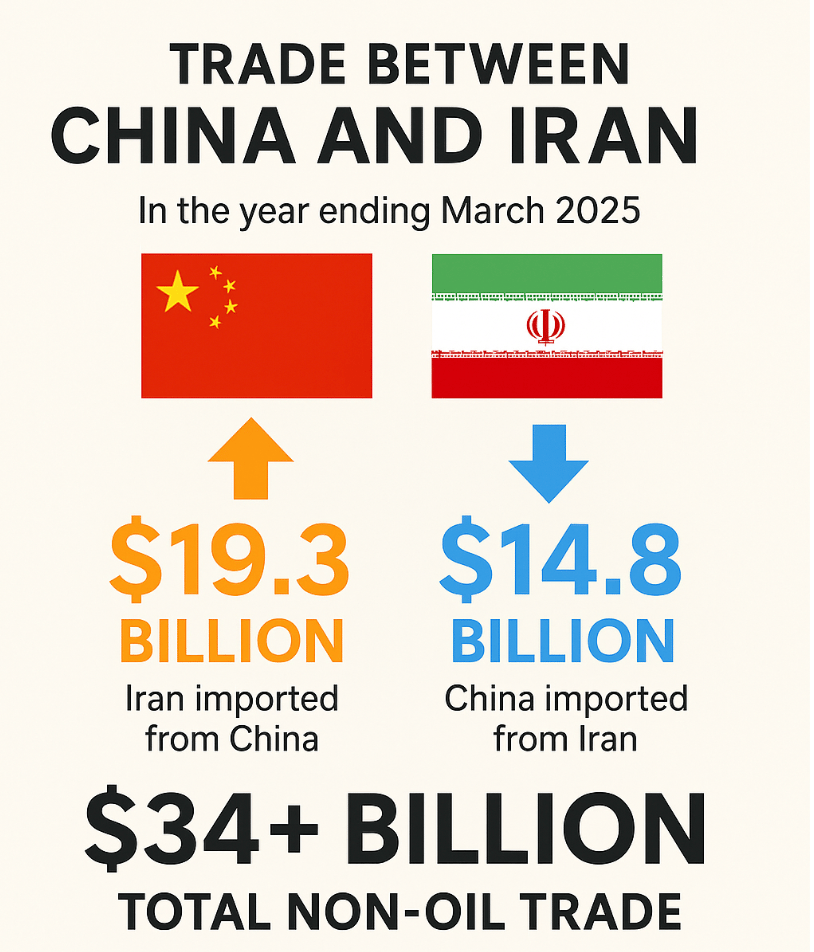

Interestingly, non-oil trade is also growing rapidly. According to Iran’s Customs Administration (IRICA), in the year ending March 2025, China imported $14.8 billion in non-oil goods from Iran, while Iran imported $19.3 billion worth of goods from China, resulting in a total non-oil trade of over $34 billion. China is Iran’s second-largest trading partner, just behind the UAE, and accounts for approximately 27% of Iran’s total imports.

The centerpiece of China and Iran’s economic partnership is the landmark 25-year Cooperation Program, a $400 billion agreement signed in 2021. More than just a trade pact, the deal laid the groundwork for long-term collaboration across energy, infrastructure, and commerce, signaling a major shift in the two countries’ relationship. The current rail corridor linking China to Iran is one of the key projects stemming from this broader strategic plan.

Friendly Path

The May 2025 train wasn’t the first instance of rail freight moving between China and Iran. That milestone was achieved in 2016, when a train from eastern China reached Tehran after a 10,000-km journey, completed in just 14 days, transporting 32 containers of commercial products. It marked a symbolic revival of the ancient Silk Road, traversing Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan along the way.

But the 2016 run was more a proof of concept than a permanent link. Geopolitical tensions and the COVID-19 pandemic stalled further momentum. But the vision lingered.

In April 2024, things resumed. Rail authorities from China, Iran, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan signed a cooperation agreement in Beijing, laying the foundation for renewed connectivity.

Then came the final jump. In May 2025, a freight train from Xi’an reached Aprin Dry Port, this time as part of a sustained and scalable corridor. It carried solar panels — the first of many shipments aimed at building long-term energy trade. Two more trains arrived on the same day, signaling that this wasn’t a one-off event.

So, what makes this new rail corridor such a game-changer?

Perks on Tracks

Let’s start with time.

Historically, trade between China and Iran has relied heavily on maritime shipping, with cargo traveling through a long and complex chain of sea routes. Goods would move from China through the Strait of Malacca, across the Indian Ocean, into the Arabian Sea, and finally the Persian Gulf — covering roughly 11,000 kilometers in the process.

The result? A shipping time of 30 to 40 days.

In contrast, the new overland rail route slashes that timeline to just 14 days, cutting transit time by nearly half. For time-sensitive cargo and faster inventory cycles, that’s a major advantage.

For example, an Iranian manufacturer sourcing components from China can now receive shipments in just two weeks instead of waiting 30 to 40 days by sea. That shorter lead time improves supply chain agility, reduces the need for high buffer stock, and helps manage inventory costs more efficiently.

On the other hand, Chinese buyers of Iranian goods — particularly perishables or time-sensitive materials — benefit from shorter delivery windows. What once took over 30 days by sea can now arrive in half the time.

Speed isn’t the only win here. This new rail route also offers something just as critical: a way around Western pressure.

For years, most trade between China and Iran moved by sea, passing through chokepoints like the Strait of Malacca and the Strait of Hormuz — both closely watched by the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet and its allies. That matters because under U.S. sanctions, anyone trading with Iran — even for non-oil goods — risks secondary sanctions from Washington.

But this new rail corridor tells a different story. It stays entirely within countries outside the U.S. sphere of enforcement — China, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Iran — making it a far less vulnerable route. For both sides, it’s more than a rail line. It’s a sanction-resistant supply chain, built to keep trade flowing irrespective of the geopolitical pressures.

As trade and energy begin to move through these new land routes, the U.S. is being left out of some of the region’s most significant economic and strategic developments.

The new rail corridor also neatly sidesteps rising costs and maritime hazards. Historically, sea routes from China to Iran have navigated through risky zones like the Red Sea. Since 2023, Houthi attacks in the Red Sea have reduced container traffic by ~90%, increased costs by 300%, and compelled ships to detour via the Cape of Good Hope, resulting in additional shipping delays and substantial fuel bills.

By comparison, the land corridor keeps cargo entirely over continental terrain. This translates to no piracy, no naval chokepoints, no higher insurance premiums, and reduced costs.

To make this corridor truly work, China, Iran, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan have agreed on competitive tariffs and shared operational standards to streamline rail services across borders.

Additionally, Iran and China are both looking to capitalize further on this route, with plans to increase their usage steadily over the coming years.

According to the CEO of Aprin Dry Port, the corridor "will reduce transportation costs and reduce reliance on coastal freight hubs." According to officials, up to 15–20% of China–Iran trade could be transported through this rail link by 2030.

The advantages go far beyond short-term trade gains — this corridor could redefine national identities and advance long-term geopolitical ambitions of both Iran and China. Let’s break it down.

Metamorphosis

The new rail corridor can empower Iran to become a transit hub connecting East Asia with the Middle East and Europe. In short, it can act as a bridge between the East and the West. And the ability to move goods across borders without relying on U.S.-patrolled sea lanes can give Tehran newfound leverage in shaping its foreign policy.

In fact, Iran can move to building a transit-focused economy that doesn’t rely so heavily on its unpredictable oil revenues. After years of being cut off by sanctions, this presents Iran with a rare opportunity to leverage its location to exert strategic influence and generate a steady income from trade routes.

For China, this rail corridor serves as a safety net — a means to reduce its reliance on high-risk sea routes, such as the Strait of Malacca, through which most of its oil passes. A land route through Iran gives China a backup option that’s less likely to be blocked or hit by sanctions, especially during conflicts.

It also helps revive the Belt and Road Initiative, which has lost momentum in Africa and Southeast Asia. Finally, if the rail line eventually connects to Europe through Turkey, China could gain a faster and more secure path to Western markets.

What’s unfolding isn’t just a shift in logistics — it’s a slow erosion of the dollar’s dominance and U.S. influence over global finance.

Dollar’s Detour

China is not just building rail tracks, it's also laying down financial tracks that bypass the U.S.-led system.

Quietly but deliberately, China has begun shifting major trade deals with partners such as Iran and Russia into yuan-based settlements, thereby avoiding the global dollar system.

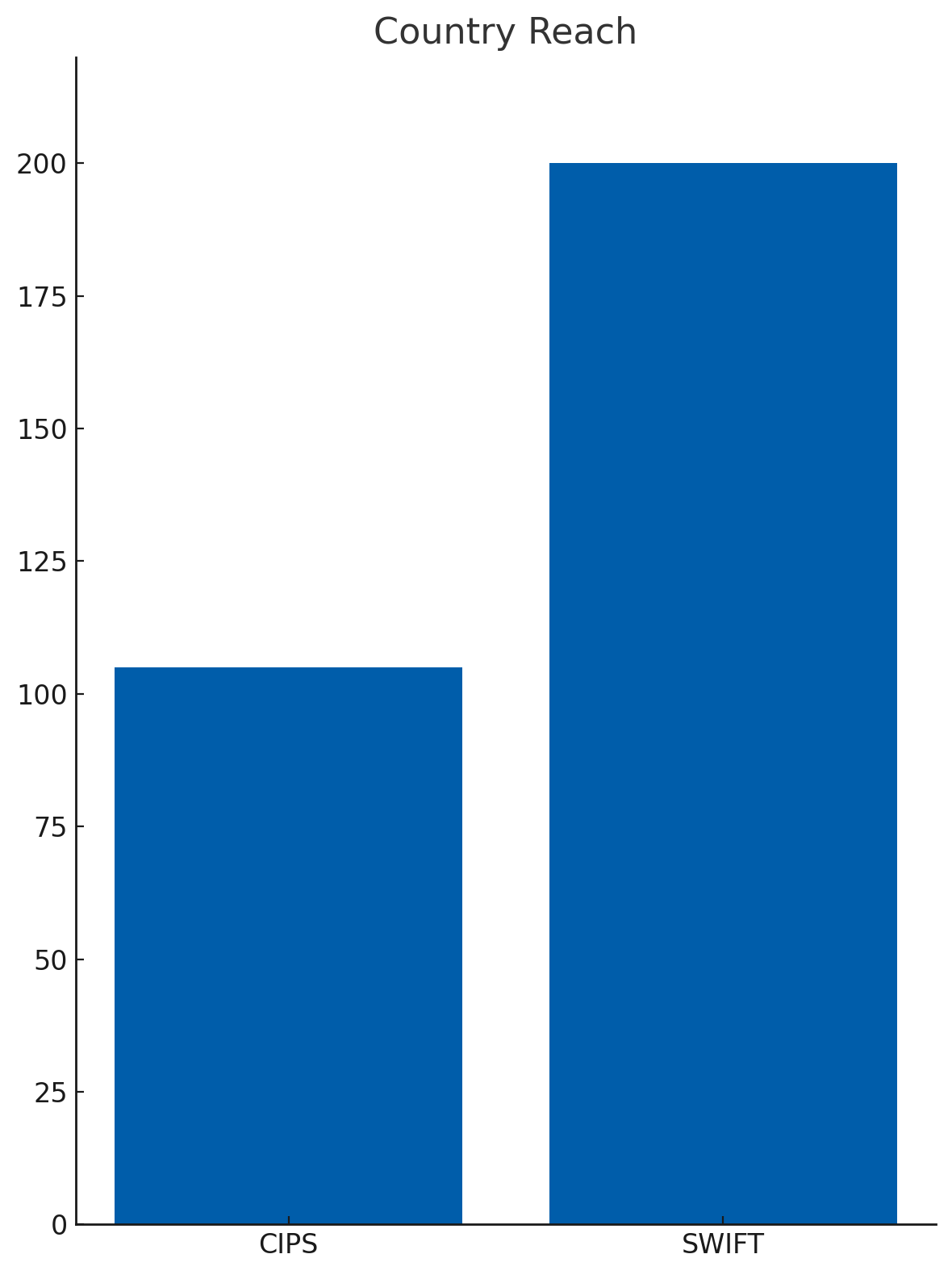

Countries using SWIFT vs CIPS

Since 2012, China has been buying Iranian oil mostly in Yuan. In 2024 alone, China purchased nearly 77% of Iran’s crude oil, valued at around $29 billion, primarily in Yuan. That same year, China–Russia trade soared past $230 billion, with the majority of payments no longer in dollars.

The corridor also chips away at the dominance of SWIFT and U.S.-dollar clearing systems, both of which have been tools of enforcement in the West’s sanctions arsenal. Iran has long been cut off from SWIFT, making even basic trade settlements painfully slow or impossible.

This is where China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) comes into the picture. In 2024, CIPS processed RMB 175.49 trillion in cross-border Yuan payments — a massive 42.6% jump from the previous year, according to China’s 2024 Payment System Report.

The system is now being tightly integrated into Belt and Road trade flows, providing countries with a reliable alternative to SWIFT. As more nations settle transactions in Yuan or local currencies, the dominance of the U.S. dollar begins to loosen — a quiet but significant shift that shows how the world’s second-largest economy is gradually strengthening its own currency and payment system.

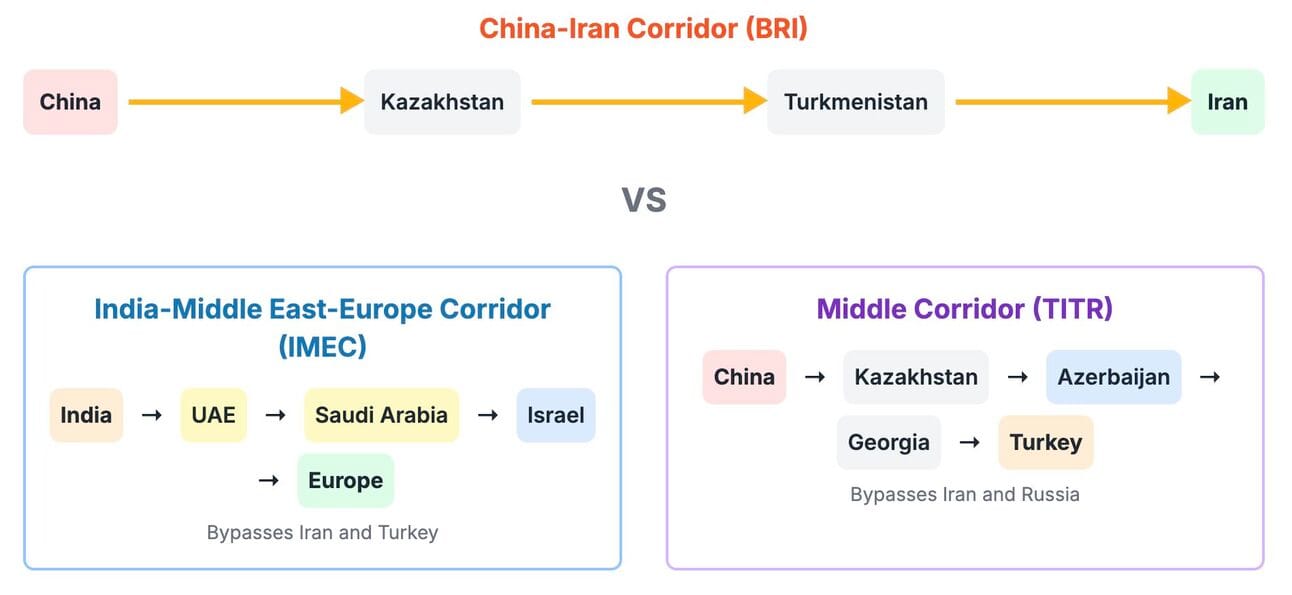

Finally, the China-Iran rail network is a direct competitor to the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), backed by the United States.

IMEC aims to connect India to Europe through a mix of maritime and rail links — shipping from Indian ports to the UAE, then overland through Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Israel, before reaching European markets via Mediterranean ports.

It’s positioned as the West’s answer to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, part of Washington’s broader strategy under the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII).

However, unlike the China–Iran corridor, which is already transporting cargo, IMEC is still in the drawing board stage.

Iran-China Freight Corridor Challenges

For all the promise the China–Iran rail corridor brings, it faces two major obstacles that limit its scalability: cost and capacity.

Let’s start with the economics. Rail does offer a speed advantage—bringing down transit time from over 30 days by sea to around two weeks over land—but that speed comes at a higher price. Industry estimates peg the cost of shipping a single 20-foot container (TEU) by rail between $1,200 and $1,800. That’s significantly higher than the $600–$1,000 it typically costs to move the same container by sea.

Then there’s capacity. Freight trains can only haul a limited number of containers per trip, and only a limited number of trips can run each day. By contrast, a single ultra-large container vessel (ULCV) can carry anywhere from 8,000 to 24,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) in a single voyage. That kind of scale simply can’t be matched by rail

Final Words

Right now, the China–Iran rail line is just one of many arteries in a sprawling trade network. Ships still do the heavy lifting. Most goods between Asia and the Middle East — or Central Asia — will continue to move by sea, at least for now. The rail line, while promising, won’t entirely replace shipping routes.

For China, it’s a backup plan — a way to keep trade flowing even when sea lanes become risky or contested. For Iran, it’s a quiet move toward something bigger: positioning itself as a connector, a middle node between Asia and Europe. Even if volumes are small today, the symbolism — and the potential — are not.

However, this development is something the world, especially the United States, should take note of, because infrastructure like this doesn’t just move containers.

According to a Wall Street Journal report, Iran has recently ordered ingredients for hundreds of ballistic missiles from China. In the future, shipments like these could move through land corridors that fall outside Western surveillance. That’s why this rail link isn’t just a trade route — it’s a strategic blind spot. And it’s one the U.S. and its allies can’t afford to ignore, not for what it carries today, but for what it could carry next.

This newsletter was written by Shyam Gowtham

Thank you for reading. We’ll see you at the next edition!