For decades, the Santa Clara Valley was known as the “Valley of Heart’s Delight”, thanks to the valley’s orchards, flowering plants, and fruit. In fact, in the 1960s, it was the largest fruit-producing and packaging region in the world.

But by the 1970s, a different kind of harvest was underway in the region.

In 1971, a journalist named Don Hoefler gave the valley a name that reflected this new reality, recognizing that it wasn't just orchards flourishing there anymore, but a revolutionary semiconductor industry that was taking root.

He called it Silicon Valley.

In that very same year, a three-year-old company in the valley called Intel released the world’s first commercially available microprocessor. This invention ignited the personal computing era and set Intel on its path to becoming one of America’s most iconic tech companies.

Nearly half a century later, the tables have turned.

Silicon Valley is no longer a major hub for large-scale semiconductor manufacturing, and its legendary resident, Intel, is now facing the worst crisis in its history, stumbling both financially and strategically in a world it once dominated.

And the new Trump administration is committed to reversing both of these.

In a landmark announcement on August 22nd, the White House declared an unprecedented move: the U.S. Department of Commerce, through the CHIPS Act fund, will take a 10% equity stake in Intel, signaling the government's effort to reshore critical technology and restore American dominance in semiconductor manufacturing.

In this issue of CrossDock, we trace the rise and fall of Intel, we break down the "why" and "how" behind the White House’s 10% stake in the company, and finally, we examine what this partnership means for Intel's future and the domestic semiconductor manufacturing industry.

Birth of Chipmaker

Interestingly, the story of Intel begins with a rebellion.

In 1956, Nobel laureate William Shockley, a brilliant but notoriously difficult manager, recruited a dream team of young PhD graduates to his Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory.

Just a year later, disappointed by Shockley's authoritarian management style, a group of eight employees did the unthinkable: they resigned en masse. This legendary group, which Shockley labeled the "Traitorous Eight," went on to establish a new company that would become the epicenter of the American semiconductor industry: Fairchild Semiconductor.

Among the rebels were Robert Noyce, the visionary co-inventor of the integrated circuit, and Gordon Moore, the chemist whose 1965 observation became the legendary Moore's Law.

A decade later, feeling constrained at the very company they helped build, Noyce and Moore left Fairchild to start their next venture along with investor Arthur Rock. In 1968, they founded Integrated Electronics, a name they quickly and famously shortened to Intel.

Intel began its journey with the production of memory chips, the equipment that stores short-term data. However, just three years after its founding, the company delivered a breakthrough that would redefine its destiny and the future of computing: the Intel 4004, the world’s first commercially available, general-purpose, single-chip microprocessor.

Intel founders Robert Noyce, Gordon Moore, and Arthur Rock

Intel Free Press, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This new innovation, coupled with the success of its 1103 DRAM (dynamic random access memory) chip — which had captured nearly 50% of the semiconductor market — had an immediate and explosive impact on the company's finances.

According to Intel's 1971 annual report, revenues more than doubled in a single year, jumping from $4.2 million in 1970 to $9.4 million in 1971. Interestingly, among Intel's earliest and most crucial customers was the U.S. government, which needed the new technology for missile systems, advanced avionics, and satellites.

However, Intel’s watershed moment arrived in 1981. For the first time, it collaborated with IBM, the undisputed king of the computing world.

IBM has always been a digital fortress, building every critical component of its massive mainframe computers in-house. But for its secretive new project to build a "Personal Computer," IBM broke its own tradition, deciding to use parts from outside suppliers to get to market quickly. For the computer's brain, IBM chose Intel's 8088 microprocessor. This decision set off two events that solidified Intel’s success for decades to come.

Firstly, IBM's choice instantly legitimized Intel's x86 architecture — the fundamental language understood by the processor — as the global standard. With the biggest name in computing giving its seal of approval, the rest of the industry quickly followed suit.

Next, IBM's PC was built with an open architecture. This allowed other companies like Compaq and Dell to create "IBM-like" clones. And to get the same performance as IBM, these companies used Intel for the microprocessor.

If Intel were the mind, the PC needed a soul. For this, IBM chose to partner with a then little-known company from Washington called Microsoft.

This decision placed both companies at the heart of every single PC: Intel provided the hardware, and Microsoft provided the software. This combination became the legendary "Wintel" platform, a symbiotic partnership that created a vise-grip on the personal computing industry for decades.

But Intel had a new challenge. Consumers knew the brand on the outside of the box (Dell, Compaq), but not the key component that was powering it. To solve this, Intel launched its 1991 "Intel Inside" marketing campaign.

The goal was to make the processor a household name, shifting the branding power from the PC makers back to Intel and cementing its dominance in the minds of millions. Soon, every single PC that housed the Intel processor came with an “Intel Inside” sticker. Intel became synonymous with computing power in the minds of millions of users.

And this reflected in their numbers.

In August 2000, Intel's stock surged to its all-time high of over $75 per share (split-adjusted), pushing its market valuation to exceed $509 billion, making it one of the most valuable companies on the planet.

Ironically, even as Intel reached its peak in 2000, the foundations for its future decline were already being laid.

Bad Intel

Intel's current problems, in a way, are not due to market forces or a rival's masterstroke, but rather a story of poor choices the chip maker made.

And none illustrates this better than the decision made in 2006, when Steve Jobs approached the company with a historic opportunity to manufacture the processor for a revolutionary new device called the iPhone.

Intel’s then-CEO Paul Otellini rejected the offer to build the new ARM-based chip that Apple wanted. He felt the iPhone would not be a high-volume business.

That turned out to be a costly mistake.

By turning its back on the iPhone, Intel didn't just pass on a single product. It let go of the opportunity to spearhead the smartphone revolution. The historic opportunity it abandoned was eagerly seized, first by its rival Samsung, and later perfected by the manufacturing powerhouse TSMC, which stepped in to build the chips that would power the next decade of technology.

And the inevitable happened: In 2011, smartphone sales surpassed PC sales for the first time, with 487.7 million smartphones shipped worldwide compared to 414.6 million PCs, according to a Canalys report.

Smartphone sales surpassed PC sales in 2011

In a 2013 interview with The Atlantic, a retired Paul Otellini reflected on the missed opportunity: “The world would have been a lot different if we’d done it.”

To better understand Intel’s fall, let’s examine its problems in two parts: a failure in designing the right chips and a failure in manufacturing them. Let’s start with manufacturing.

For decades, Intel’s golden rule was that it must both design and build its own chips. The company believed this vertical integration gave it total control and a massive advantage over competitors. For a long time, they were right.

But around 2014, this strength became a weakness.

Intel’s legendary factories, once the best in the world, started falling behind schedule. The company got stuck for years trying to produce its new, more advanced "10-nanometer" chips. The delays were so bad that the once-reliable cycle of releasing faster chips every couple of years came to a halt.

Much of this delay occurred because Intel hesitated to adopt extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography, a more advanced technology that simplifies the manufacturing of smaller nodes and improves yields, due to its high costs and perceived immaturity at the time.

While Intel was stuck, its rivals saw an opportunity, especially TSMC. The Taiwanese company focused on becoming ruthlessly efficient at just one thing: manufacturing chips for other companies. This business model, coupled with relentless execution and early adoption of next-generation technologies such as extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography, enabled them to consistently deliver smaller, faster, and more power-efficient chips.

By the time Intel could finally mass-produce its 10nm chips, TSMC was already rolling out superior 7nm and 5nm chips for the entire world.

The end result?

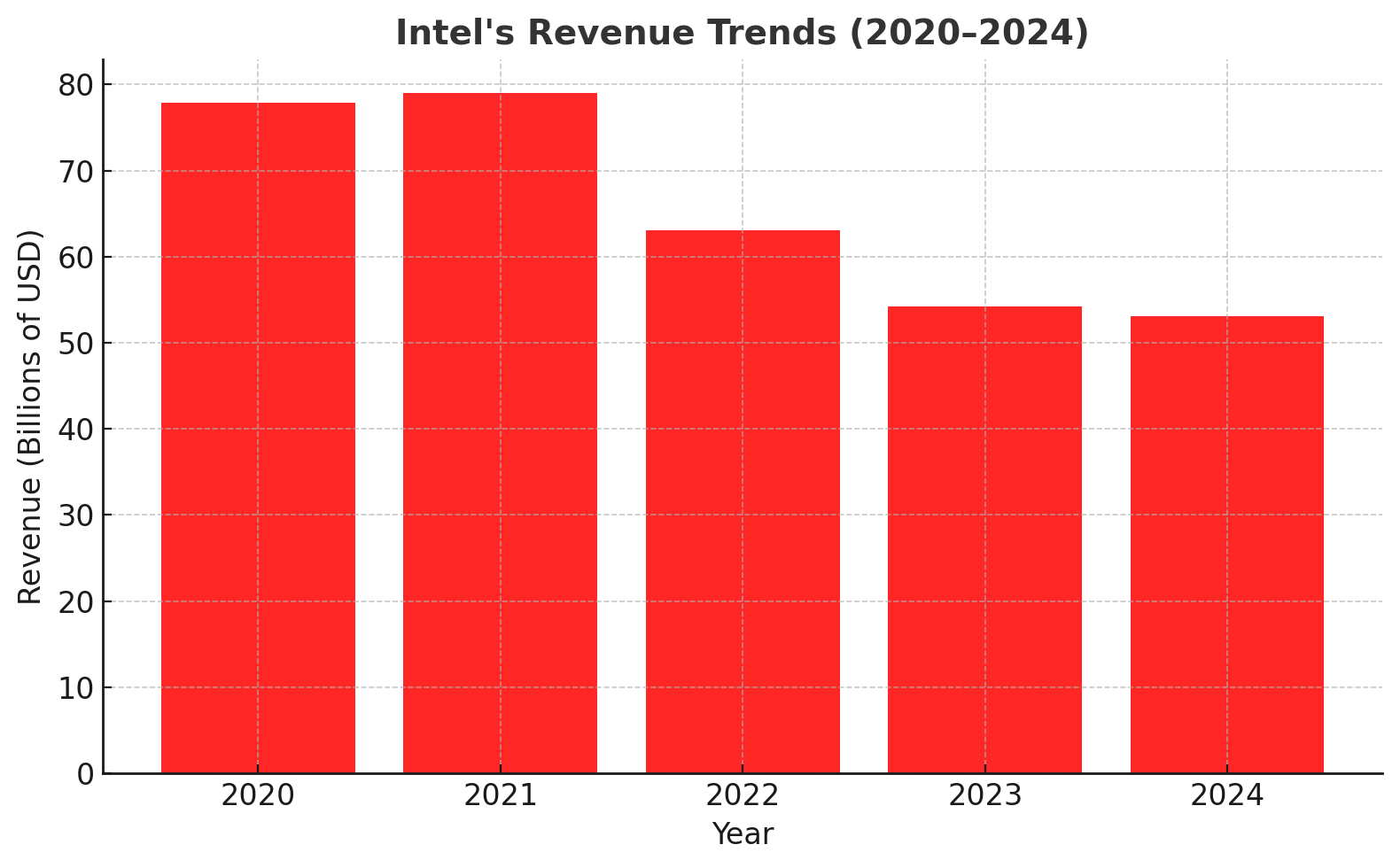

In 2022, TSMC's revenue surged to approximately $75.9 billion, a significant leap from its previous year, while Intel's revenue for the same year declined to $63.1 billion. This marked the first full year in which TSMC's revenue surpassed that of Intel.

At the same time, Intel was making an even bigger mistake in its design labs, and it completely missed the AI revolution.

Blinded by the decades-long success of its CPUs — chips brilliant at solving one complex problem at a time — Intel’s leadership failed to grasp the new paradigm of parallel computing.

They reportedly passed on acquiring a rising NVIDIA for around $20 billion and even pulled the plug on their own promising GPU projects.

Intel failed to predict that the AI revolution would be built on GPUs (Graphics Processing Units), which act like a massive army of processors working in parallel, a perfect fit for AI's immense workloads.

When OpenAI’s ChatGPT triggered the AI boom, Nvidia was in the right place at the right time — its GPUs became the beating heart of the AI revolution. The result: the company’s market capitalization soared past $3.3 trillion by mid‑2024, and it became the first public company to reach $4 trillion in value by mid‑2025.

Meanwhile, 2024 was one of Intel’s worst years in recent memory. The company reported a 2% drop in full-year revenue to $53.1 billion. What’s worse, Intel’s big bet on its Gaudi 3 AI chips fell flat in 2024, bringing in less than $500 million in sales. By contrast, Nvidia’s AI chips generated more than $40 billion in the same year — a gap that shows just how far behind Intel is in the AI race.

However, what’s more concerning is its lackluster performance in sectors it once dominated.

For example, according to a report by Mercury Research, released by AMD, Intel’s once-dominant position in its traditional strongholds — PC processors and data center chips — has weakened significantly.

Just a few years ago, Intel outsold AMD in desktop CPUs by nearly 9-to-1; however, by Q2 2025, its market share had fallen to approximately 67.8%. The data center side tells a similar story: Intel’s server CPU share has slipped to around 62%, down sharply from its near-total control in previous years.

Coincidentally, Intel’s decline from an American icon to a struggling chipmaker overlapped with Washington’s push to reshore semiconductor manufacturing.

Powered by Policy

The centerpiece of this new industrial policy was the CHIPS and Science Act, a massive government fund designed to incentivize companies to build semiconductor factories on U.S. soil.

Under the Biden administration, Intel became the program's flagship recipient. In March 2024, the Commerce Department announced a landmark deal to provide the company with up to $8.5 billion in grants and $11 billion in loans to fuel its ambitious plans to build massive new fabrication plants in Arizona and a "Silicon Heartland" in Ohio.

What started as a government subsidy program under one administration has now evolved into a strategy of taking direct ownership under the next.

On August 22nd, 2025, in a late-night post on his Truth Social platform, President Trump declared that the U.S. government would acquire a 10% equity stake in Intel.

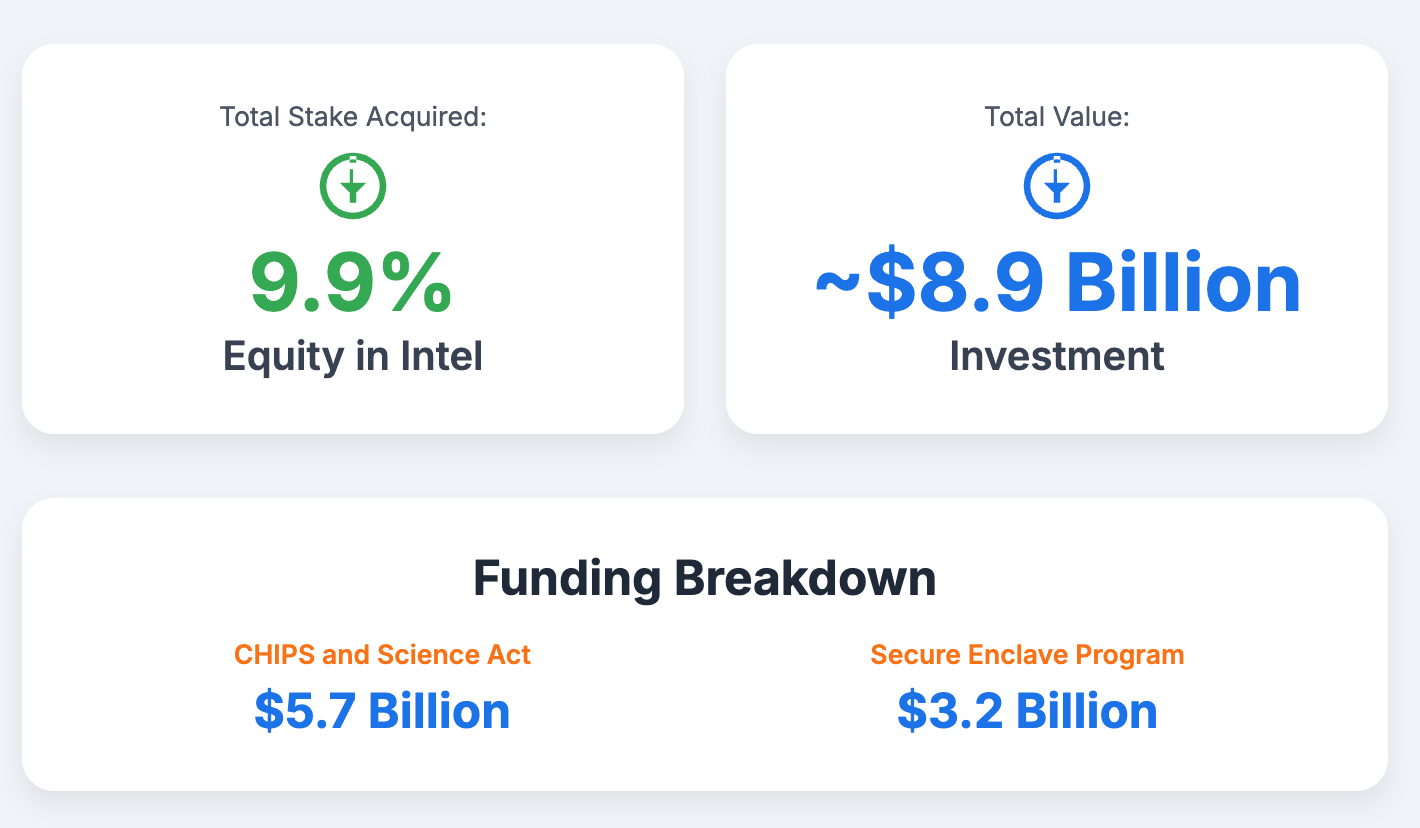

According to the White House, the U.S. government will acquire a 9.9% stake in Intel, valued at approximately $8.9 billion. Of this, $5.7 billion will come from the CHIPS and Science Act, and $3.2 billion from the Secure Enclave program. This is in addition to the $2.2 billion Intel has already received under the CHIPS Act, making it one of the biggest federal investments in a U.S. tech company.

But why Intel?

Intel is the only U.S. semiconductor company that carries out advanced R&D and high-end manufacturing in the US, with the capability to compete directly with giants like TSMC and Samsung. And the White House sees Intel’s survival as essential for national security.

In his latest interview with CNBC, Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick said, “We want Intel to be successful in America. We like an American semiconductor built in America, and we would like an American company to be doing that.”

Regarding the 10% stake, he added: “We think America should get the benefit of the bargain.”

However, experts are not pleased with the deal; in fact, Intel is not entirely confident about this latest arrangement. Let’s take a look at that.

Future Hurdles

Intel has shared its concerns in its latest SEC filing, warning that the company’s landmark deal with the U.S. government comes with significant risks.

For example, the company states that by converting CHIPS Act grants into equity ownership, Intel could lose access to billions in potential government funding over the coming years. Other agencies might also hesitate to provide new grants or push for similar equity-based arrangements, which could raise Intel’s cost of capital and increase long-term operating expenses.

The filing also highlights shareholder and global risks. The U.S. government is buying its stake at a discount, meaning immediate dilution for existing investors.

On the global front, 76% of Intel’s revenue comes from outside the U.S., including 29% from China, and having Washington as a major shareholder could trigger foreign regulations, subsidy restrictions, or political pushback.

Intel also warns of possible negative reactions from investors, employees, international partners, and regulators as the company navigates this unprecedented move.

Some analysts view the U.S. government’s 10% stake in Intel as a clear departure from traditional free-market principles, marking a shift toward state-driven industrial policy.

Adding to the debate is a five-year warrant in the deal that allows Washington to buy an additional 5% stake if Intel ever spins off its manufacturing arm — a clause critics say could discourage strategic restructuring moves, like separating its foundry business, that might have helped accelerate Intel’s turnaround.

At the same time, the U.S. government’s 10% stake in Intel is also being seen as a huge positive for the company’s future.

For one, it signals strong domestic backing, which strengthens Intel’s positioning in the U.S. market and boosts confidence among suppliers, partners, and investors. Markets have already reacted favorably — Intel’s stock price jumped nearly 6% after the announcement — suggesting renewed optimism about the company’s turnaround.

Adding to that momentum, SoftBank is preparing a $2 billion investment in Intel, bringing in fresh capital and validating the company’s long-term growth potential. Together, these moves indicate that Intel is not only stabilizing but potentially entering a new phase of recovery and expansion.

Final Words

In recent months, the U.S. government has become far more active in shaping the future of critical technologies and strategic industries.

Through tariffs and industrial policies, Washington has already drawn in massive investments from global players like TSMC and Samsung to expand semiconductor manufacturing in America. But alongside foreign commitments, it’s equally important to have a strong domestic champion, and this is where Intel becomes central to the strategy.

This move also fits into a broader pattern of state-backed interventions, such as the government’s equity stake in MP Materials to secure rare earth supply chains and its “golden share” in Nippon Steel to protect domestic interests. Together, these actions signal a clear trajectory: the government is positioning itself as an active participant in rebuilding America’s industrial base and securing its technological edge.

However, there’s a delicate balance to maintain. While government involvement can strengthen national security and resilience, it’s equally important that these stakes don’t distort free-market dynamics that define the American economy.

This newsletter was written by Shyam Gowtham

Thank you for reading. We’ll see you at the next edition!