On July 11, President Donald Trump announced a new wave of retaliatory tariffs, and Brazil was among the countries in his crosshairs. Trump pointed to what he called a “witch hunt” against former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro as well as unfair trade practices as the reasons behind the move.

Interestingly, the U.S. actually ran a $6.8 billion trade surplus with Brazil in 2024 — meaning it exported more to Brazil than it imported. In fact, the U.S. hasn’t run a trade deficit with the South American country since 2007.

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva didn’t hold back in his response. Taking to X, Lula warned that Brazil would retaliate if the U.S. moved ahead with the tariffs.

The world watched as two countries locked in a trade tussle.

But amidst all this, a new friendship is quietly growing stronger.

China and Brazil have forged a largely unnoticed but increasingly strategic friendship. What began as commodity-driven trade has evolved into something deeper.

In this issue of CrossDock, we are breaking down the Brazil-China trade relationship over the years. We also take a look at sectors and industries that are impacted by this friendship. Finally, we also examine what this means for the United States.

Band of Brothers

Brazil in the 1970s was still under the iron claw of a military dictatorship. It was a period of severe political repression — freedom of speech was curtailed, opposition was silenced, and the press was tightly controlled.

Ironically, this was also the decade the country witnessed an extraordinary economic boom, later dubbed the “Brazilian Miracle.” Between 1968 and 1973, Brazil’s GDP grew at an average annual rate of over 10%.

Similarly, in China during the 1970s, the country was under strict political control, though its internal struggle looked very different from Brazil’s. China was enduring the tumultuous final years of the Cultural Revolution, a decade-long political campaign launched by Mao Zedong.

But in China, economic growth stalled as ideology took priority, and China became even more isolated from the global community. But China’s long spell of international isolation began to change in 1972, when its door to global diplomacy was opened by a man who stepped off Air Force One.

President Richard Nixon’s visit to Beijing was the first time a U.S. president had set foot in the People’s Republic of China.

President Richard Nixon Shaking Hands with Chairman Mao Tse-tung

Soon, other countries followed, especially Brazil.

Just two years later, in 1974, Brazil formally established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China. But the relationship remained largely symbolic through the next two decades.

Throughout the 1980s, total annual trade between the two countries stayed well below $1 billion, with China accounting for less than 1% of Brazil’s total foreign trade. The limited exchange mostly involved basic raw materials and low-value goods, with little to no movement of advanced machinery or finished products.

By contrast, the United States remained Brazil’s dominant trading partner during this era. According to U.S. Census Bureau data, U.S.–Brazil trade totaled over $10.6 billion in the 1980s.

But it was in the 2000s that the China–Brazil relationship truly took off, fueled by trade, after China joined the Elite Club of global trade — the World Trade Organization.

Trade Partners

By the early 2000s, China’s economy was booming, and so was its population and rising middle class. More people meant more demand for meat, and more meat meant more livestock to feed. To meet that demand efficiently and at scale, China turned to the most reliable source of animal feed: soybean meal.

But there was a catch here. China had a very limited domestic soybean production.

That is because China’s arable land is simply too limited to meet its massive soybean demand through domestic production alone.

As Ke Bingsheng, former president of China Agricultural University, told CGTN: “China’s arable land is simply too limited to meet its massive soybean demand through domestic production alone. Even if all the farmland in the north and northeast were dedicated to growing soybeans, yields would average only about 120 kilograms per mu (roughly 0.067 hectares).

According to the American Soybean Association, in 2000, China produced 15.7 million metric tons of soybeans, amounting to 9% of the global soybean production that year. However, its demand was skyrocketing.

Blessings come in many forms. For China, it came in the form of the WTO.

In 2001, after China joined the WTO as a condition of its membership, China committed to significantly lowering its tariffs or removing them altogether for a wide range of goods. This included agricultural imports like soybeans.

That same year, China became the world’s largest importer of soybeans. It imported nearly 14 million metric tons of soybeans, most of which were from the US and Brazil.

The soybean trade opened the floodgates for a much broader commodity relationship between China and Brazil.

China's rapid industrialization demanded not just food for its people, but raw materials for its factories and infrastructure boom. Soon, Brazil began providing iron ore for China's massive steel industry and construction projects, crude oil to fuel its energy-hungry economy, copper and other minerals for manufacturing and electronics, and pulp and paper products for its growing consumer market.

Let’s explain this better with the iron ore industry.

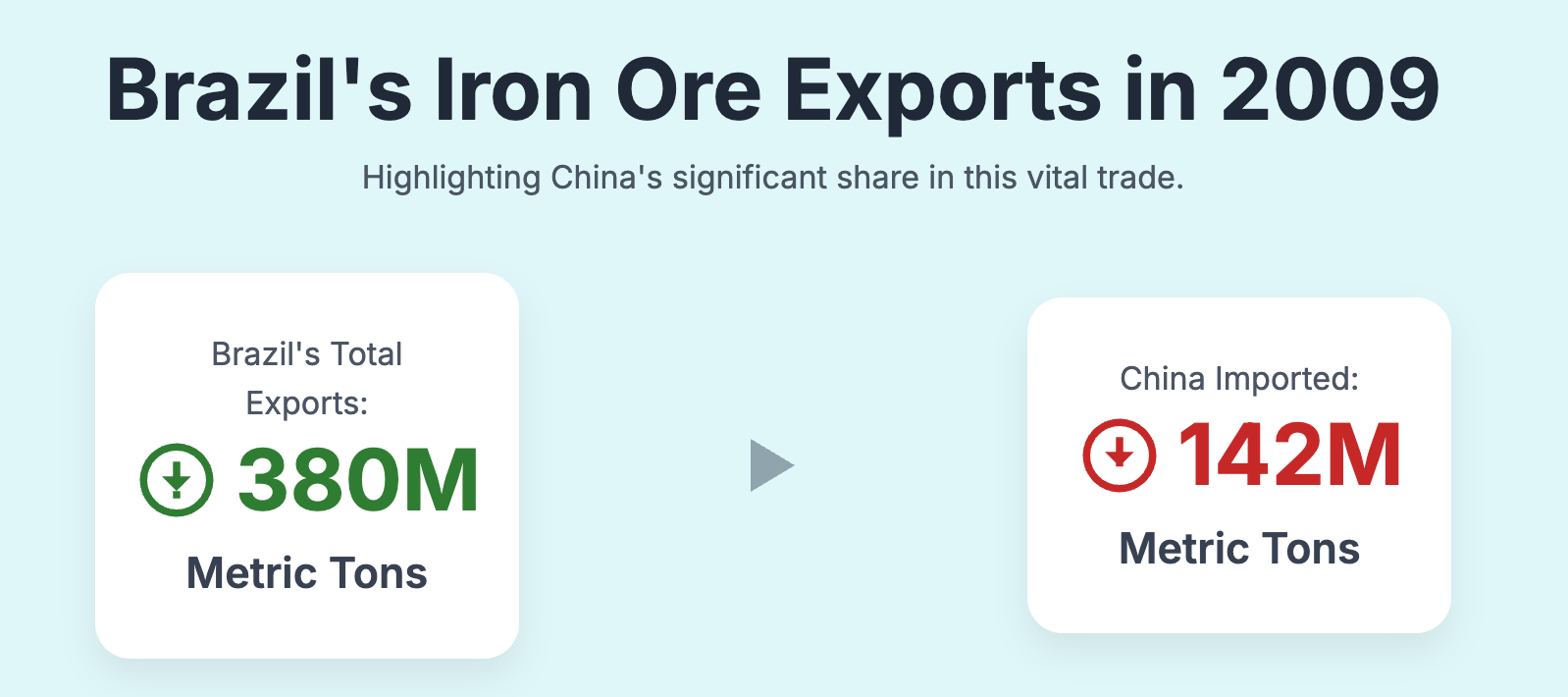

Despite being the world’s biggest iron ore producer between 2001 and 2009, China rapidly emerged as the largest buyer of Brazilian iron ore to meet its industrialization needs.

According to USGS, by 2009, Brazil’s total iron ore exports had risen to 380 million tons, but the real story was China. That year, China imported nearly 142 million tons – a big chunk of Brazil’s production. According to World Integrated Trade Solutions data, Brazil exported more than $10.5 billion worth of non-agglomerated iron ore and concentrates in 2009, with China absorbing the lion’s share of that trade.

But the crown jewel of the Brazil-China trade was still soybeans.

In 2009, China was Brazil’s largest customer for soybeans, purchasing around 16.3 million metric tons — nearly 57% of Brazil’s total soybean exports that year.

This surge in trade between Brazil and China culminated in two major events.

First, in 2009, China officially became Brazil’s largest trading partner, overtaking the United States for the first time. Bilateral trade reached $36 billion that year — a figure that had tripled in just five years and which was just less than $2 billion a decade back. Brazil recorded a trade surplus of $4.3 billion with China in 2009.

Here’s how the trade looked: Brazil sent commodities like soybeans and iron ore, while China shipped manufactured goods. In fact, 98% of Chinese exports to Brazil were manufactured products. Meanwhile, minerals and soybeans made up two-thirds of Brazil’s exports to China.

The deepening ties were also visible in corporate procurement patterns. According to a Reuters report, the number of Brazilian companies purchasing over $50 million worth of goods from China surged from just 12 firms in 2005 to 41 in 2009.

Overall, the number of Brazilian importers sourcing from China more than doubled, jumping from about 7,158 in 2005 to 16,853 by 2009 — a clear reflection of China’s growing footprint in Brazil’s domestic supply chains.

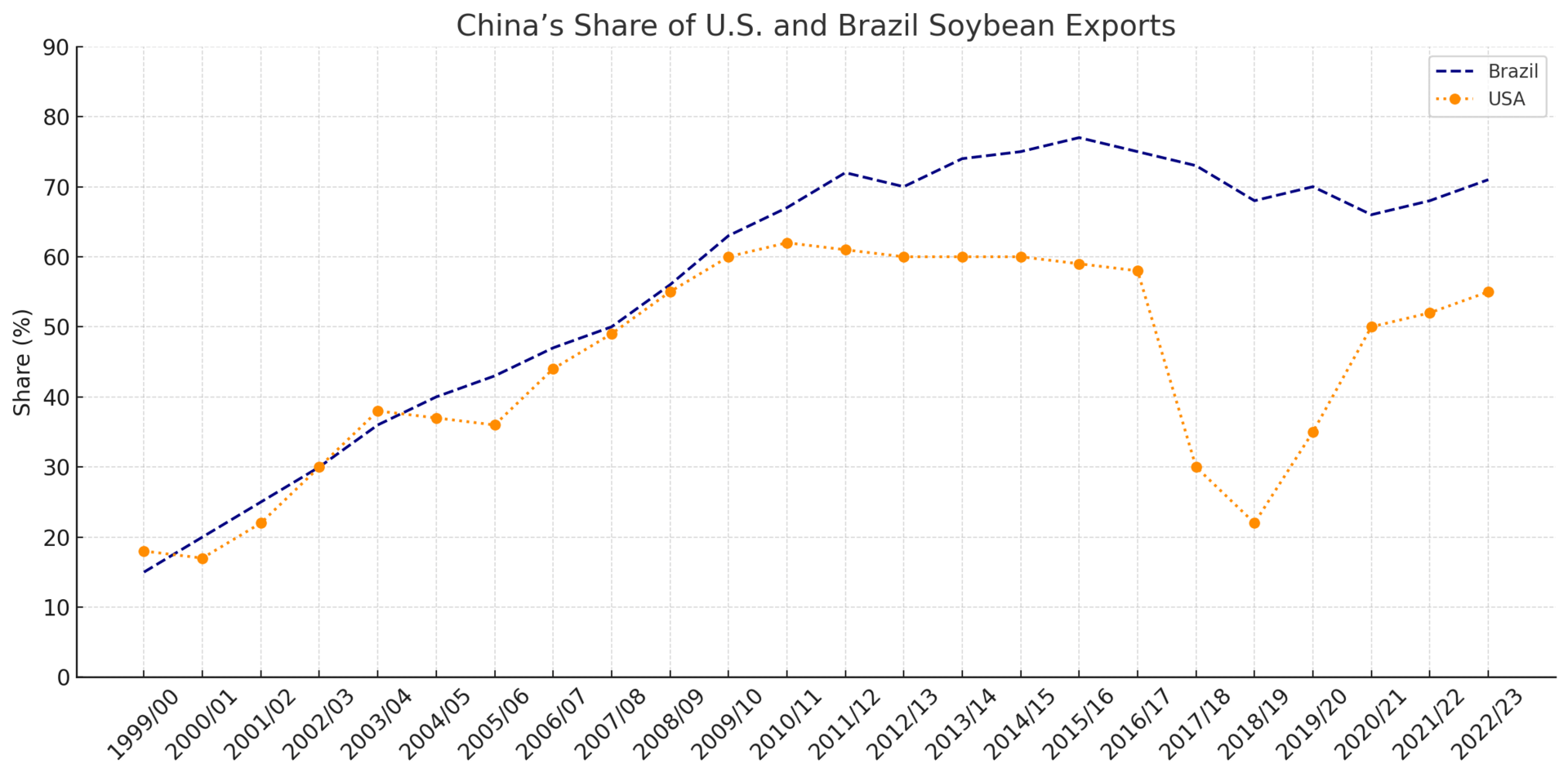

The second major event also involved the dethroning of the US. In 2009, for the first time, the United States’ soybean exports to China declined. Over the next four years, this trend deepened, and by 2013, Brazil overtook the U.S. as China’s top soybean supplier. According to the USDA, Brazil exported approximately 1.8 billion bushels of soybeans in 2013 to China, while the United States exported around 1.4 billion bushels.

Price played a crucial role in this change. For instance, Brazilian soybeans were often cheaper than those from the U.S., thanks to lower labor costs, a weaker Brazilian Real, and less stringent export regulations. Brazilian suppliers were also seen as more flexible in pricing and contracts.

Secondly, Brazil’s soybean exports were also reportedly free from certain GMO restrictions imposed by China that sometimes complicated U.S. exports. For example, in 2014, China returned over 1 million tons of U.S. corn due to the detection of MIR162, a GMO ingredient not approved by China's Ministry of Agriculture.

However, Brazil’s position as both the world’s largest soybean exporter and China’s top supplier was firmly cemented in 2018, when the U.S.–China trade war pushed Beijing to shift away from American agricultural imports. Let’s break that down for you.

Tariff Battles

In his first presidential term, the prime target of his trade policies was China. He stated that the $418 billion trade deficit (at that time) with China was due to unfair trade practices, intellectual property theft, forced technology transfers, and poor deals made by previous governments.

To reduce the $419 billion trade deficit with China, President Trump, during his first term, imposed tariffs on $360 billion worth of Chinese goods. China hit back swiftly, with tariffs of its own. It chose an area that could do the most damage to the US: American agriculture.

Beijing immediately slapped retaliatory duties on U.S. soybeans, pork, and other farm exports. The impact was immediate. According to a USDA research report, the tariffs resulted in nearly $26 billion in lost U.S. agricultural export value, with soybeans alone accounting for 71% of the total loss. In just one year, agricultural exports to China plunged 76%, dealing one of the most severe blows to U.S. farmers in recent times.

And Brazil filled that void.

Brazil captured approximately 76% of China's soybean import market, while the U.S. share plummeted to just 19%. This dramatic shift solidified Brazil’s dominance in supplying soy to China. Interestingly, the very next year, in 2019, Brazil overtook the United States as the world’s largest soybean producer.

Even after a trade truce was reached, Brazil has continued to hold 70–75% of China’s soy market, while the U.S. has struggled to recover to pre-tariff levels.

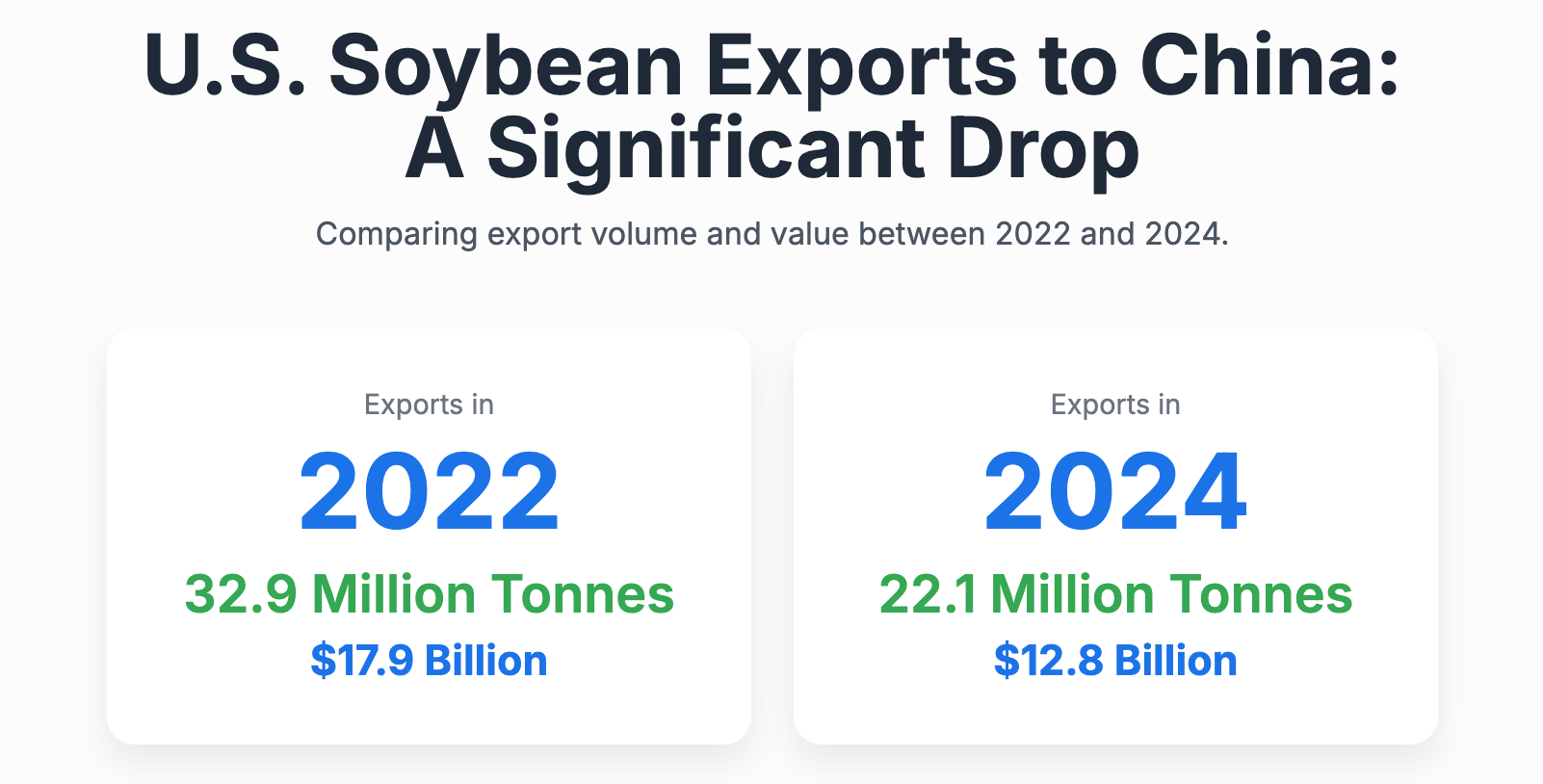

U.S. soybean exports to China dropped from 32.9 million tonnes in 2022 to just 22.1 million tonnes in 2024, with export value falling from $17.9 billion to $12.8 billion.

China’s share of U.S. soybean exports shrank to 21% in 2024, the lowest in over a decade.

In 2024, China imported a record 105.03 million metric tons of soybeans, with Brazil alone supplying 74.65 million tons—accounting for nearly 71% of the total. This means more than two-thirds of China’s soybean needs are now met by Brazil, reflecting a major shift in sourcing strategy

So, what does this mean for US farmers?

The combination of reduced access to the Chinese market and growing competition from Brazil in other export destinations is putting heavy downward pressure on U.S. soybean prices. Current projections indicate that soybean prices could fall to $410 per metric ton in 2025, representing a 15% year-over-year decline. Prices are already hovering just below $400/ton, marking a 15% drop from previous highs.

For U.S. farmers, the drop in soybean prices means shrinking profit margins and rising financial pressure. But the impact goes far beyond the fields. According to the USDA’s Economic Research Service, soybean exports support approximately 231,400 jobs, with soybean meal exports contributing another 41,400. These exports fuel employment not just on farms, but across manufacturing, logistics, services, and trade.

Let’s now touch upon the 50% tariff on Brazilian imports.

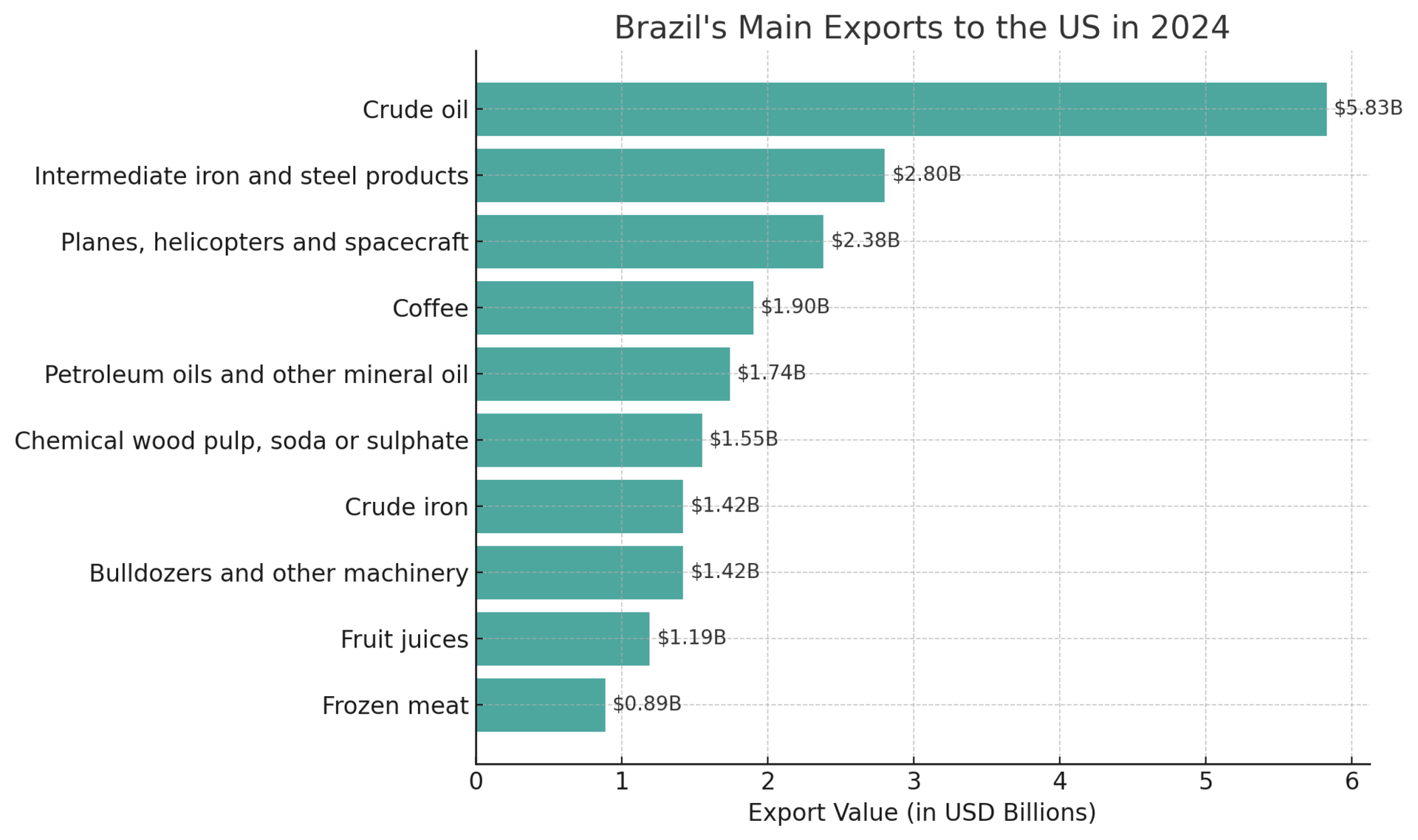

In 2024, total U.S. goods trade with Brazil reached an estimated $92 billion, with imports accounting for $42.3 billion of that volume. The U.S. sourced a wide range of products from Brazil — including fuels (like crude and refined petroleum), iron and steel, machinery, coffee, and agricultural goods. And these imports are going to be more expensive.

Take orange juice, for example. Brazil is the world’s largest exporter, and it supplies well over half of all the fresh orange juice Americans drink, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. As of June 2025, prices for frozen orange juice concentrate were already up 5.5% year-over-year. Now, with a proposed 50% tariff on Brazilian orange juice, the prices can skyrocket further.

The story’s similar for coffee. Brazil is the world’s largest coffee producer, and it supplies about 30% of all the coffee imported into the U.S. Tariffs on coffee imports can make the drink even more expensive.

Beyond agriculture, sectors like energy, infrastructure, and digital technology are also drawing renewed strategic investment and attention in the China–Brazil relationship.

Let’s move on to that.

Giant Ports

When Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Brazil in 2025 — his first trip to the country in five years — he was welcomed with full ceremonial pomp. Xi’s official state car was flanked by a cavalry of 120 dragoons, and a marching honor guard stood in salute. In his address, he declared: “The China–Brazil relationship is at its best period in history… but the most wonderful chapter is yet to come.”

Over the past decade, China has poured billions into Brazil’s logistics, ports, and railways, transforming the country's agri-export corridors into vital arteries for Beijing’s food security.

In Santos, Latin America’s largest port, China’s state-owned grain trader COFCO is building its largest export terminal outside China — expanding capacity from 4.5 million tons to 14 million tons annually. The $285 million terminal project, slated to reach full capacity in 2026, will handle corn, sugar, and soybeans, with 30% of all Brazilian soy already destined for China, currently flowing through Santos.

In addition to this, China is laying hundreds of miles of rail across Brazil’s farming belt, creating direct links between inland soybean fields and key export ports.

Another recent infrastructure development that’s worth noting is the 2,800-mile Transcontinental Railway. China and Brazil have signed an MoU to conduct a feasibility study for one of South America’s most ambitious projects.

The line would connect Brazil’s Atlantic coast to the Chinese-funded Port of Chancay in Peru, effectively creating an overland Atlantic–Pacific trade route. If completed, it could cut shipping time to Asia by 10–12 days, bypassing the Panama Canal.

After ports and soybeans, China’s next big bet in Brazil is Electric Vehicles.

The EV Pivot

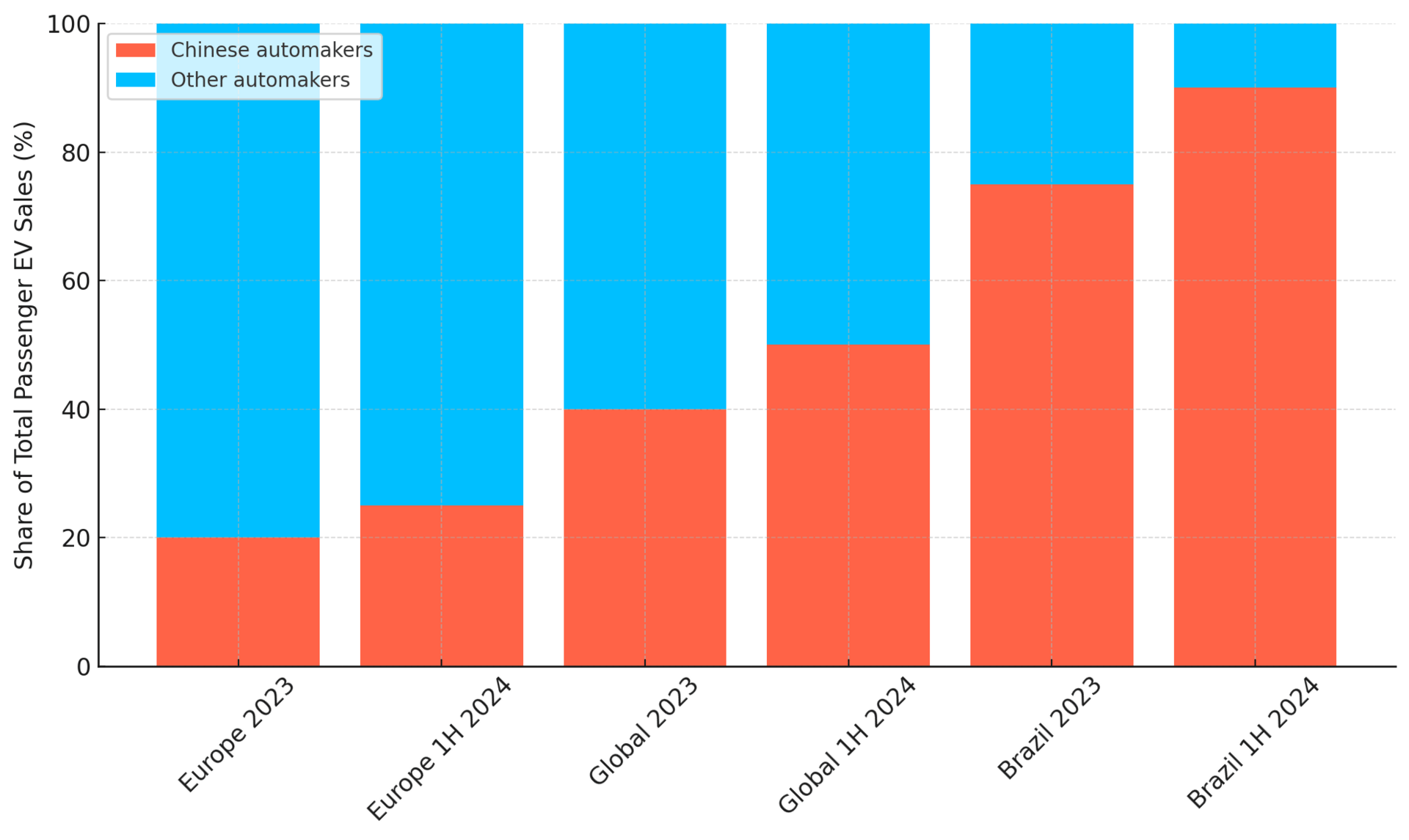

With the U.S. cracking down on Chinese electric vehicles and the EU moving to impose tariffs of its own, Chinese automakers have turned to a more welcoming market: Brazil. It is Latin America’s largest economy and the sixth-largest car market in the world.

Brazilians love their cars, and for decades, American, European, and Japanese brands dominated the streets and factories. But today, Chinese EVs are rising fast. Between 2023 and 2024, imports of Chinese-made vehicles into Brazil tripled, according to Brazil’s National Association of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers.

BYD, Great Wall Motor, and Chery are leading the charge — not just shipping vehicles, but building them. BYD, the world’s top EV maker, is opening one of Latin America’s largest electric car factories in Bahia. Great Wall took over a former Mercedes-Benz plant. And Chery, in partnership with local player Caoa, is ramping up production in Goiás state.

In addition to the EV companies, Chinese big tech is also eyeing Brazil for growth and expansion.

Big Eyes

With China’s domestic economy under pressure from a collapsing real estate sector and consumers tightening their wallets, many of its biggest firms are looking abroad. At the same time, rising trade tensions with the U.S. and EU have made it more costly and politically risky to grow in traditional export markets. That’s where Brazil comes in – the biggest market in Latin America that embraces global brands.

In the last few years, a wave of Chinese consumer giants has launched, expanded, or announced their plan to operate in Brazil. For example, Meituan, China’s largest food delivery app, announced a $1 billion investment to establish operations. Mixue, now the world’s biggest fast-food chain by store count, is hiring thousands to expand its bubble tea and dessert empire across Brazilian cities.

Interestingly, TikTok, which is facing scrutiny in the U.S. and U.K., launched its Brazilian marketplace in May 2025. Similarly, Temu began selling to Brazilians last year.

So, what does this growing friendship mean for the US?

Cautionary Tale

For the U.S., the growing friendship between China and Brazil is a warning sign. By slapping tariffs on Brazil, Washington may be pushing Latin America’s biggest player closer to Beijing. The signs are clear. China and Brazil are now doing more of their trade in yuan instead of dollars, and Brazil just announced it’s opening a tax advisory office in China.

Even without officially joining the Belt and Road Initiative, China has poured over $70 billion into Brazil. For 15 consecutive years, China has been the biggest trade partner of Brazil. But experts say this goes beyond trade. It’s starting to look like a real shift in global influence. China is building deep roots in Brazil, a region that was once aligned with US interests.

And this could not be more evident than in the words of Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva: “Brazil and China will be indispensable partners… China needs Brazil, and Brazil needs China. Together, we can make the Global South respected in the world like never before.

This newsletter was written by Shyam Gowtham

Thank you for reading. We’ll see you at the next edition!