Good morning readers,

Every technological revolution is built on physical materials that most people never see. Railroads needed steel. Electrification depended on copper. Today, the AI boom depends on one such commodity: optical fiber, which transmits data at light speed within data centers.

At the center of this is the 175-year-old Corning, a company that has quietly powered multiple technological revolutions long before this one.

In this issue of CrossDock, we trace the journey of Corning’s optical fiber, its role in the AI boom, how it is reshaping the trajectory of this legendary company, and why it now sits at the very center of the global AI infrastructure buildout.

In 1957, the credit rating company Standard & Poor’s introduced the S&P 500, a benchmark that tracked 500 of the largest publicly traded U.S. companies. It was designed to give investors a clearer, broader measure of the American stock market.

Nearly seven decades after its creation, the S&P 500 is now synonymous with America’s economic strength. Yet fewer than 10% of the original 1957 companies remain in the index. Among that shrinking group is a company nearly a century older than the index itself: Corning.

When historians write about Corning, they will likely settle on three truths: the company was in the right place and at the right time. But more importantly, it made the right products.

In fact, it is that third truth that has enabled the company to survive for 175 years.

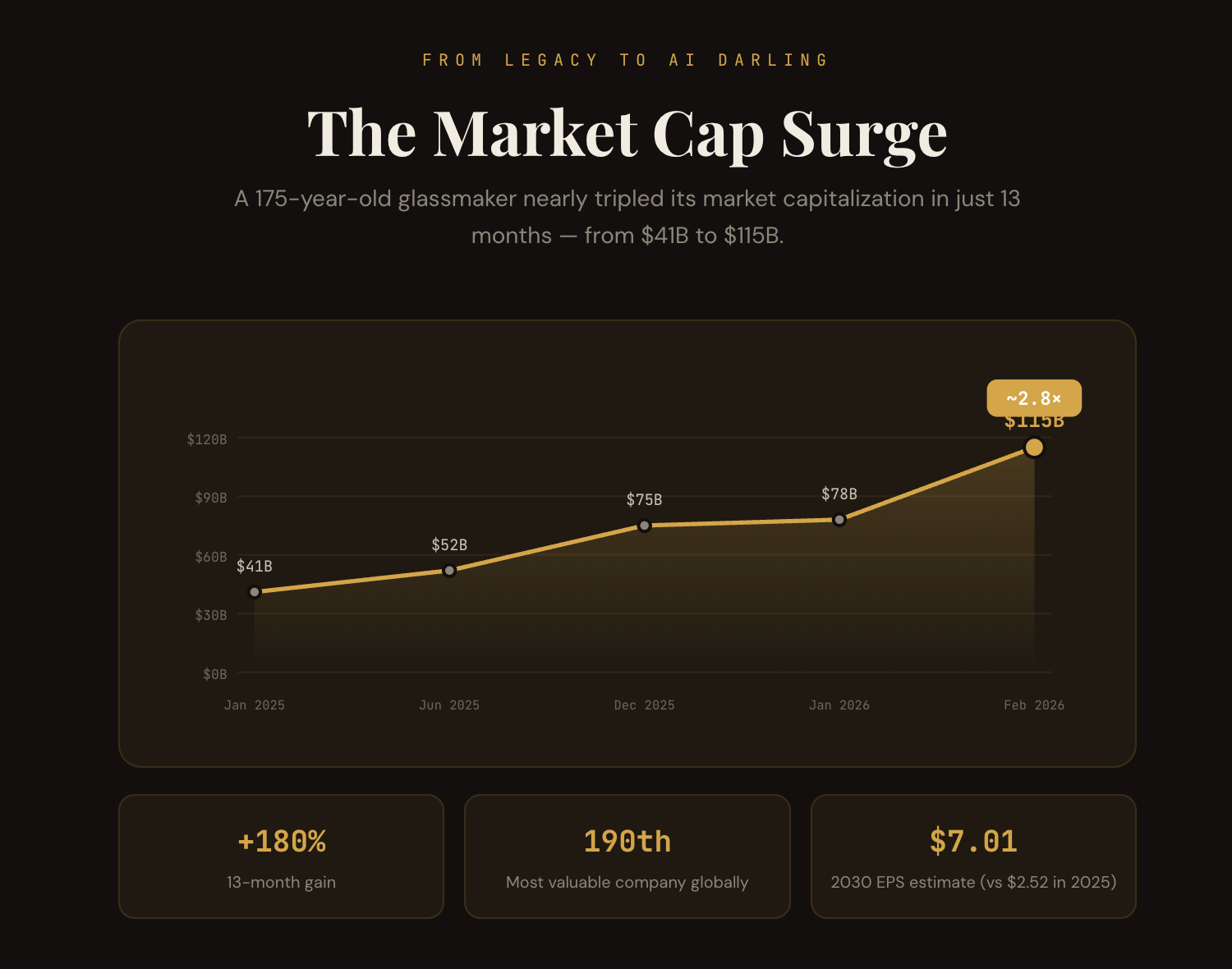

The company’s recent 2025 Q4 results are a testament to this. In Q4 2025, the company’s revenue climbed to $4.41 billion, up 14% year over year, while the stock has surged roughly 60% over the past three months, including a 42% gain in the last month alone, making Corning the 6th best-performing stock in the S&P 500.

So what’s behind Corning’s stellar performance? The answer lies in the burgeoning AI buildout.

Corning’s optical fibers now sit at the center of surging demand from Big Tech, including Meta, Nvidia, OpenAI, Google, Amazon, and Microsoft, all racing to expand data center capacity and AI infrastructure.

To understand all of this better, we need to go back in time — to the origins of optical fiber — and see how a materials science breakthrough decades ago quietly laid the foundation for today’s AI infrastructure.

Castle of Glass

Corning Glass Works was founded in 1851 by Amory Houghton in Somerville, Massachusetts, originally as the Bay State Glass Company. It was later relocated to Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where it operated as the Brooklyn Flint Glass Works. Finally, in 1868, the company moved to its permanent home in Corning, New York — the city that would eventually give the company its name.

The company's biggest breakthrough came in 1879, when a 32-year-old inventor, Thomas Edison, approached Corning to make a specialized glass for his light bulbs. He wanted a glass that could protect the fragile filaments inside his experimental lightbulb. He needed material that was stronger, more heat-resistant, and precisely manufactured. By 1880, Corning had become the sole supplier of glass envelopes for his bulbs.

This early collaboration set the pattern for what would define the company for the next century: engineering glass at the frontier of technological change.

1917 advertisement for the Corning Conaphore headlamp lens

In 1915, it developed borosilicate glass—marketed as Pyrex—that could withstand extreme temperature changes, revolutionizing kitchenware and laboratory equipment. During World War II, it manufactured glass for military aircraft and optical equipment. In the 1960s, it produced the glass windows for NASA spacecraft, including those used in the Apollo missions. In the 2000s, it made the famous Gorilla Glass for iPhones.

So every time the market matured or technology shifted, Corning found a new application for glass. Within the company, this approach became the “Corning Way.”

In the 1970s, history presented the company with another opportunity to go the Corning Way.

Optical Revolution

For most of human history, glass was simply a material for windows, bottles, and decorative objects. The ancient Egyptians made glass beads as early as 3500 BCE, and the Romans perfected glassblowing techniques.

But no one imagined it would transfer data.

In the 1960s, global telecommunications was reaching its limits. Copper cables could only carry so much information, and long-distance signals weakened quickly, requiring frequent amplification. As demand for phone calls and data transmission grew, the existing infrastructure struggled to keep up.

Charles Kao, a British-Chinese physicist working at Standard Telecommunication Laboratories in England, proposed a radical idea: Instead of sending electrical signals through copper, he proposed sending light through glass. He said light could travel through ultra-pure glass fibers over long distances with minimal signal loss. In 1966, he published a paper demonstrating that if signal loss in glass could be reduced below 20 dB/km—a measure of how much light fades per kilometer—it would be possible to transmit information over practical distances.

But the claim seemed impossible to achieve. Glass fibers at the time lost so much signal that light barely traveled a few meters before disappearing.

Yet in 1970, four years after Kao's audacious paper, researchers at Corning achieved exactly what the skeptics dismissed: an optical fiber with a loss of 17 dB/km, low enough to transmit light over practical distances. This single invention became the backbone of global telecommunications and made the World Wide Web possible.

Corning suddenly had a product that could change telecommunications. The only question was whether anyone would use it.

At first, they wouldn't.

When Corning tried to sell fiber to telecom companies in the early 1970s, most executives dismissed it. The world's infrastructure ran on copper wire and coaxial cable.

Switching to glass would require replacing millions of miles of existing networks. AT&T, the dominant American telecom monopoly, viewed fiber as interesting research but impractical for deployment.

Corning spent the next decade proving them wrong. The company filed hundreds of patents, refined manufacturing processes, and reduced costs.

But it was the Dot-com boom of the 90s that truly turbocharged Corning's growth.

The internet was emerging. Bandwidth demand was exploding. Email, web, and browsing all needed more capacity. At that time, telecom experts projected that internet traffic would double every 100 days. To make it all possible, the world wanted more optical fiber, and Corning had it.

During this period, Corning became one of the most important companies in the telecommunications supply chain. Between January 1998 and September 2000, Corning’s stock surged more than 700% — climbing from roughly $10 to $113 — as demand for fiber optic infrastructure accelerated during the internet buildout.

Sadly, when the dot-com bubble burst in 2000, it all came crashing down.

The Fall

When the dot-com bubble burst, demand for fiber collapsed, and Corning was hit hard in its core business.

Anticipating a global telecommunications expansion, Corning had put too many eggs in one basket: the optical fiber division.

Between 1999 and 2000, Corning had gone on an acquisition spree. The company spent billions buying its way deeper into telecommunications: $1.8 billion for Oak Industries, $1.4 billion for Siemens' optical cable businesses, and $2 billion for NetOptix Corporation. Additionally, according to the earnings report, Corning poured roughly $4 billion into property, construction, and expansion, hoping optical fiber demand would continue to grow.

But when the dot-com bubble burst, most of its biggest customers went bankrupt. Fiber-optic sales, which had represented 40% of Corning's revenue in 2000, plummeted post the burst.

In 2001, after 120 consecutive years of paying dividends — through wars, recessions, and depressions — Corning failed to pay its shareholders. By October 2002, its shares had lost 99% of their value, falling below $1.10. Multiple rounds of layoffs followed, cutting thousands of workers from the payroll. Three manufacturing plants were shuttered as orders evaporated.

For the next two decades, Corning's fiber optics division saw little growth. The pandemic brought a brief spike in demand as remote work drove connectivity needs, but it faded quickly.

However, Corning's next big moment came in November 2022, when OpenAI released ChatGPT, marking the start of the generative AI race.

As they say, history, once again, was repeating itself. Another technological boom was taking shape, and Coring was well-positioned to reap the benefits.

Glass Race

The race among Big Tech to build the best generative AI is creating unprecedented demand for more optical fiber.

A single AI data center requires approximately 2,000 to 5,000 kilometers of ultra-pure glass fiber for internal connectivity between servers, storage systems, and network switches.

So why do AI data centers need massive amounts of optical fiber?

The answer lies in operations. The way they move data is fundamentally different from traditional computing infrastructure.

Old data centers were built for north–south traffic. A user sends a request. A server processes it. A response goes back out. Most of the movement happened between the outside world and the server rack. Internal communication was secondary.

But AI data centers work differently.

Training large language models or multimodal systems requires thousands of GPUs working in parallel. They don't just compute independently. They constantly exchange data, synchronize it, and coordinate every training step. That coordination happens internally, inside the facility.

This is called the east–west traffic, and in AI clusters, it dominates the network. In many facilities, 70–90% of all traffic never leaves the data center. This is what is driving the fiber demand.

For example, according to Corning, Meta's Louisiana data center campus requires 8 million miles of optical fiber, enough to circle the Earth 320 times.

So, to keep pace with data center growth, humongous amounts of optical fiber are needed. According to Industry research from RVA LLC, approximately 92,000 route miles of new fiber infrastructure will be needed over the next five years just to keep pace with data center growth.

Today, the multibillion-dollar data center investments announced by Big Tech now depend on Corning and its optical fibers. As the largest fiber-optics maker by multiple measures and the dominant supplier to North American AI data centers, Corning wanted to leverage this opportunity.

In its Q4 2023 earnings call, Corning unveiled the Springboard plan — a multi-year push to strengthen the business by the end of 2026. The goal is straightforward: add more than $3 billion in annualized sales and reach a 20% core operating margin, using Q4 2023 as the starting point.

But Springboard is more than a margin target. It is Corning’s way of securing long-term demand. The company’s aim was to align with structural growth trends—especially the AI-driven expansion of data centers and the rising demand for high-density optical fiber—to drive steady volume growth and improve profitability over time.

And it has worked. The Springboard plan has transformed data center fiber into its fastest-growing revenue segment.

The numbers tell the story: in Q3 2025, the company's Optical Communications division generated $1.65 billion in sales—a 33% year-over-year increase—with net income surging 69% to $295 million. The growth was driven almost entirely by AI infrastructure, as hyperscalers deployed what Corning calls "Gen AI products" in their enterprise networks. Corning now projects that data center interconnect alone will become a $1 billion business by the end of the decade.

Add to this its upcoming partnerships.

In early 2026, the company announced a $6 billion deal with Meta to supply fiber-optic cable for Meta's rapidly expanding AI data centers, the largest single contract in Corning's history. Corning’s stock surged 16% after the announcement — its strongest single-day gain in more than two decades.

The company is negotiating similar deals with other hyperscalers. Meanwhile, it's developing what could be its next breakthrough: co-packaged optics with Nvidia, which would place fiber directly inside servers rather than just connecting them.

It is worth noting that the Meta deal is more than just a big contract. It shows how hyperscalers are changing the way they build AI infrastructure. Meta is securing guaranteed supply, priority manufacturing, and custom fiber designs—all while protecting itself from supply chain disruptions. This is the same strategy they used for AI chips and power: lock down critical resources years in advance.

This brings us to the most important question: Is Corning the only company capable of doing this at the moment?

Homemade Wires

The short answer is no. Corning does have competitors. Japanese manufacturers such as Fujikura and Furukawa Electric are major global fiber producers. So why can't American hyperscalers simply source from other suppliers? In fact, Fujikura and Furukawa Electric produce similar high-quality optical fibers, and Chinese companies like YOFC offer massive capacity and competitive pricing.

The answer lies in policy and safety. The U.S. government's stance on AI infrastructure is clear: domestic manufacturing matters

This gives Corning a bigger advantage: approximately 90% of the fiber it produces for U.S. customers is manufactured domestically, primarily in North Carolina and Texas.

For hyperscalers seeking federal support, tax credits, or permission to build in strategic locations, sourcing from a company with deep U.S. manufacturing roots is not just convenient; it's about being strategic. Additionally, domestic manufacturing reduces regulatory risk and supply-chain exposure.

Also, as AI data centers become critical national infrastructure, domestic manufacturing, assured capacity, and long-term reliability matter more than marginal price differences. And this is another core strength of Corning: its vertical integration. It outsources almost nothing. The company designs and builds many of the machines used to manufacture its own optical fiber and cable, giving it tight control over quality, costs, and production scale.

Final words

It is no exaggeration to call Corning an American success story. With a 175-year legacy, few industrial companies have endured this long, and even fewer have remained relevant.

What has kept Corning alive for nearly two centuries isn’t luck. It’s the instinct to move with markets, to rethink glass when the world changes. From supplying glass for Edison’s lightbulb to inventing Gorilla Glass for smartphones and pioneering breakthroughs in optical fiber, Corning hasn’t merely made materials. It has helped build the physical backbone of successive technological eras.

The current AI demand has only accelerated this legendary company's growth. As Corning notes, it took nearly half a century to produce its first billion miles of optical fiber. The second billion took just eight years. The next billion will come even faster.

This newsletter was written by Shyam Gowtham