It’s a match made on earth — quite literally — the Midwest and soybeans.

Every September, soybeans planted across millions of acres in Iowa, Illinois, Missouri, and Indiana are harvested as the plants turn dry and golden. The crops are loaded onto barges and sent down the Mississippi River — the main artery carrying the Midwest’s harvest to the world.

The soybeans are then delivered to export terminals in New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and Mobile, where they are prepared for shipment overseas. Some harvests are sent by rail to the ports of Tacoma and Seattle, then across the Pacific.

Soybeans aren’t just another American farm export.

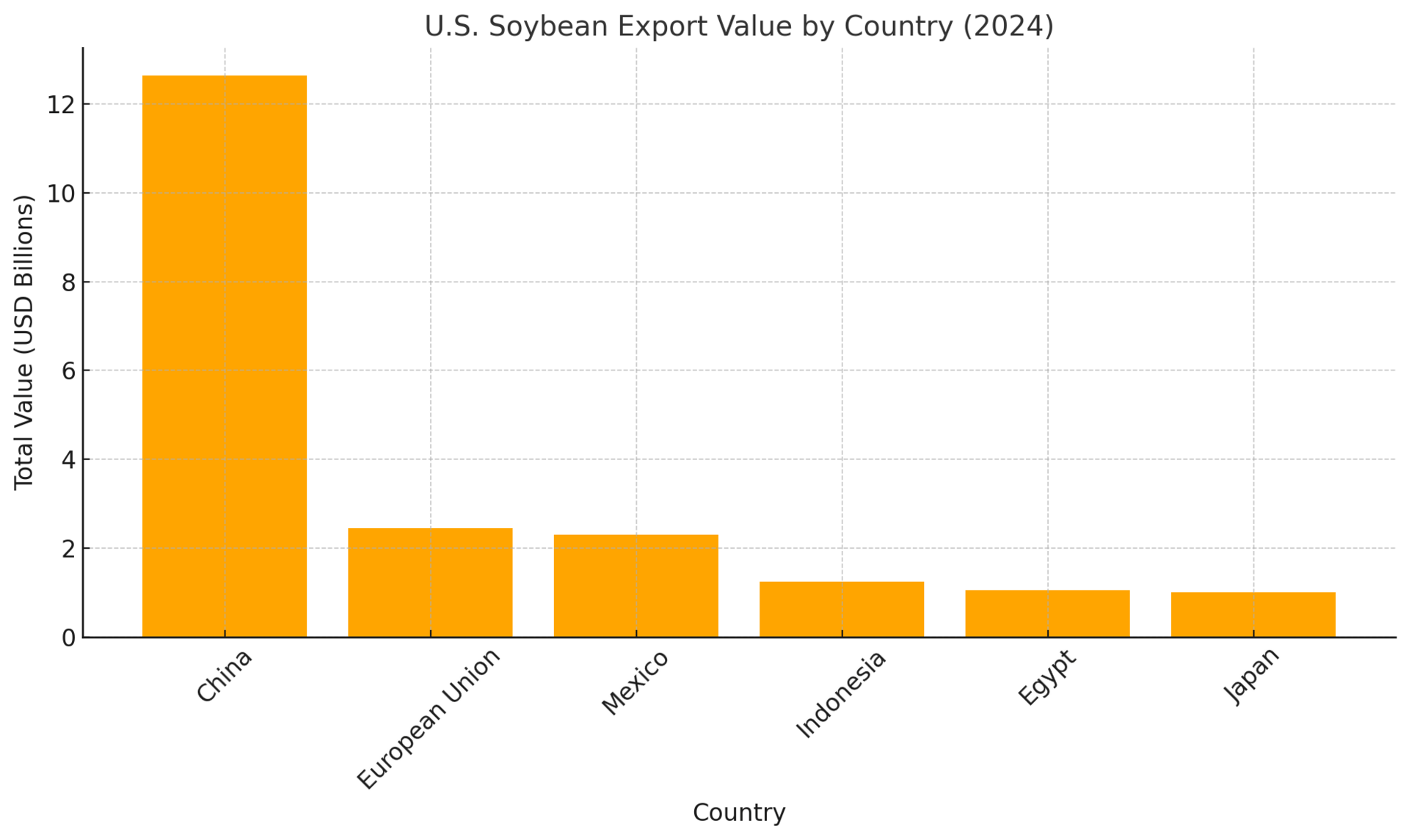

It is the second largest crop in the U.S., averaging around 85 million planted acres. In 2024, soybeans were America’s largest agricultural export, accounting for about 14% of all U.S. farm goods sent overseas and totaling roughly $24.6 billion, according to data from the United States Department of Agriculture.

Cut to the present. The pods have dried, but the optimism around U.S. soybean farming is now fading.

Millions of bushels of soybeans now sit idle, filling on-farm silos, grain elevators, and temporary storage piles across the Midwest.

Every love story needs a villain. For the Midwest and its soybeans, it came in the form of a trade war with the US's biggest customer: China.

In a typical year, China purchases between 28 and 36 million metric tons of American soybeans. In fact, last year, it bought roughly $12.85 billion worth, making it the single largest buyer of the crop.

But now, this vital soybean trade between Washington and Beijing is under strain, thanks to the US-China trade war.

According to Chinese customs data, China imported no soybeans from the United States in September 2025 — the first time shipments fell to zero since November 2018.

In this issue of CrossDock, we break down the U.S.–China soybean trade — how it became vital for American farmers, and how tariffs and trade tensions are reshaping that relationship and disrupting the soybean supply chain.

To understand the current crisis, we need to look back at how the United States built its soybean industry around China.

Rise of Soybean

The U.S.–China soybean trade story is a mix of policy, timing, and demand aligning perfectly.

The 1973 Farm Bill marked one of the most important shifts in modern U.S. agricultural history — and it quietly accelerated America’s rise in soybean production. Passed in the wake of a global food price crisis, the law introduced target prices and deficiency payments, guaranteeing farmers a minimum income when market prices fell below a set benchmark.

This safety net encouraged more production across key crops, and soybeans quickly emerged as one of the biggest winners. Thanks to ideal growing conditions and large-scale mechanization, the Midwest made soybean farming simpler, faster, and more efficient than competing crops. This made soybeans, a rotation crop, into a major export commodity that would define U.S. agriculture for decades to come.

The numbers tell the story: between 1970 and 1979, U.S. soybean acreage expanded by nearly 40%, according to USDA data.

In the same decade, across the Pacific, China was slowly opening its economy after years of economic isolation. In 1977, it imported U.S. soybeans for the first time, and by 1980, it was importing around 810,000 metric tons of U.S. soybeans.

Interestingly, China’s dependence on imported soybeans wasn’t the result of limited farmland — it was a policy choice.

Since the late 1970s, Beijing has prioritized grain self-sufficiency, focusing its most fertile land on rice, wheat, and corn. Soybeans, which yield far less per hectare and offer lower economic returns, were pushed to marginal regions. Rather than diverting lands from staple grains, China turned to imports.

And that’s where the United States, with plenty of soybeans, fits perfectly — a trade relationship that was a win for both sides. In fact, the American Soybean Association began to see China’s 1 billion people as the next big market for U.S. soybeans. This relationship only grew stronger when the rest of the world formally let China join the big boys’ trade club — the WTO in 2001.

This was also the time when China’s economy was booming and the Chinese population was rapidly growing. More people meant more demand for meat, more meat meant more livestock to feed, and hence the demand for soybeans.

Luckily, as a member of the WTO, China could now import more soybeans, with fewer trade barriers and lower tariffs than ever before.

The result? China’s soybean imports hit a record 20.3 million tons in 2003, with the United States supplying nearly 7.7 million tons — making it China’s largest source of soybean imports at the time, according to the USDA.

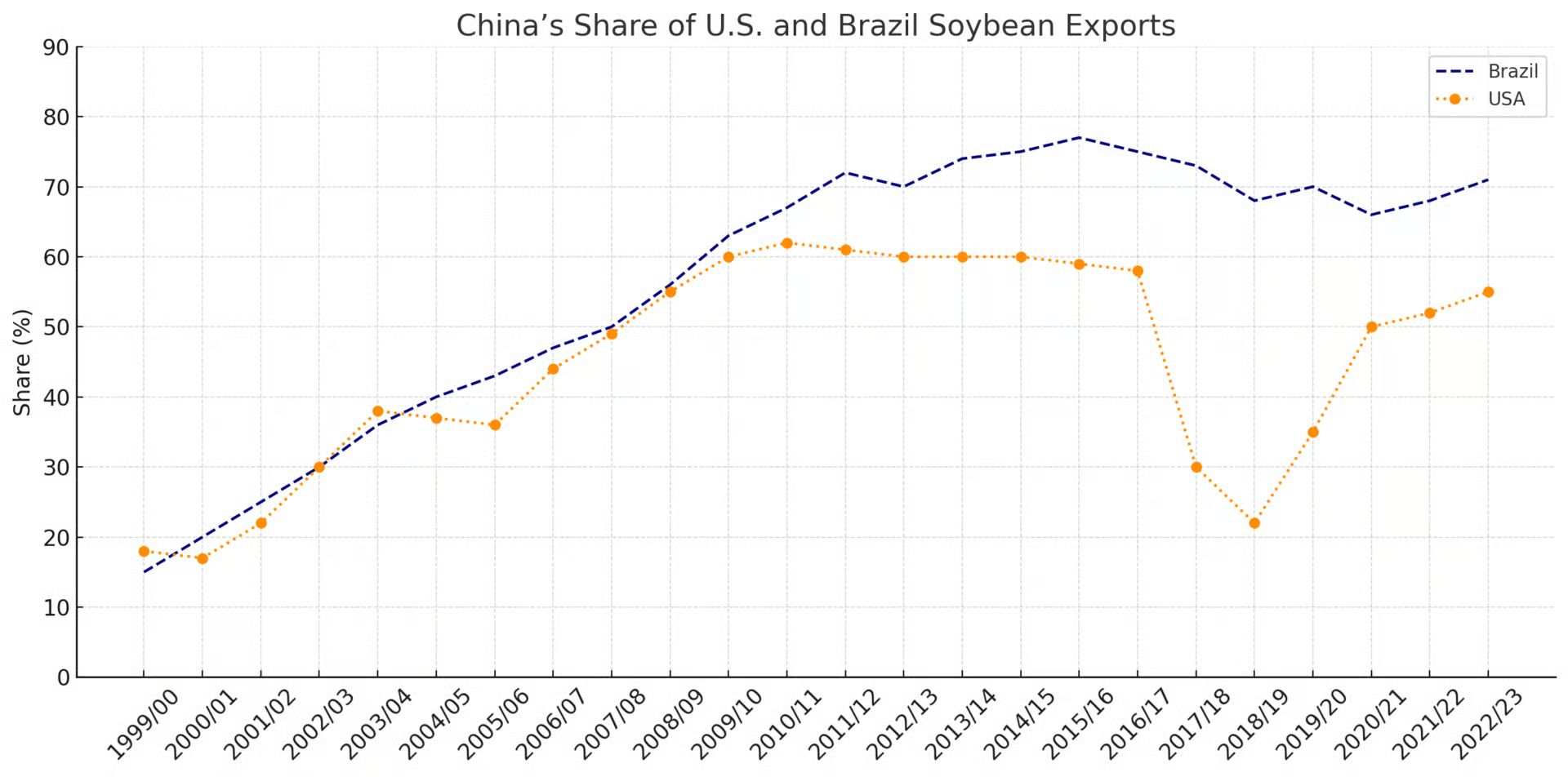

Through the 2000s and 2010s, China consistently accounted for 50–60% of all U.S. soybean exports, according to USDA data. At its peak in 2016, U.S. soybean exports to China reached 36 million metric tons, worth more than $14 billion.

But it all changed in 2018, with the advent of Trump and tariffs.

Collateral Damage

When Donald Trump, in his first term, kicked off the US-China trade war, soybeans were the first and most brutally hit. In retaliation for U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods, Beijing imposed a 25% tariff on American soybeans. The impact was immediate: According to a USDA research report, the trade war wiped out nearly $26 billion in U.S. agricultural export value, with soybeans alone accounting for 71% of the total loss.

Before the tariffs, the U.S. shipped about $12.8 billion worth of soybeans to China every year. But once the trade war hit, that number collapsed — falling to $4.7 billion in 2018/19 and just $5.8 billion in 2019/20, according to the American Soybean Association.

After nearly two years of tariff battles and collapsing exports, Washington and Beijing decided to end the trade war and signed the Phase One trade deal in January 2020. The agreement committed China to purchase an additional $200 billion worth of U.S. goods over two years, including a major boost in soybean exports.

But the COVID pandemic hit the world, and none of these actually materialized.

History repeats itself, they say — and it seems true for the U.S. soybean story. Now, in his second term, the Trump administration is once again locked in a trade tussle with China, and soybeans are back at the center of the dispute.

Grain War

In the current U.S.–China trade war, both countries are playing to their strengths. The United States, as China’s largest export destination, has leaned on tariffs — using them as leverage to secure better trade terms. The Trump administration is now threatening to raise duties to as high as 155% starting November 1, in a bid to pressure Beijing back to the table.

China, meanwhile, is flexing its own power where it matters most — in minerals and soybeans. It has already imposed export controls on key critical minerals and technology metals. It is using its status as the world’s largest soybean buyer and America’s biggest customer as a strategic bargaining chip. Since the renewed trade tensions began, Beijing has sharply scaled back purchases of U.S. soybeans.

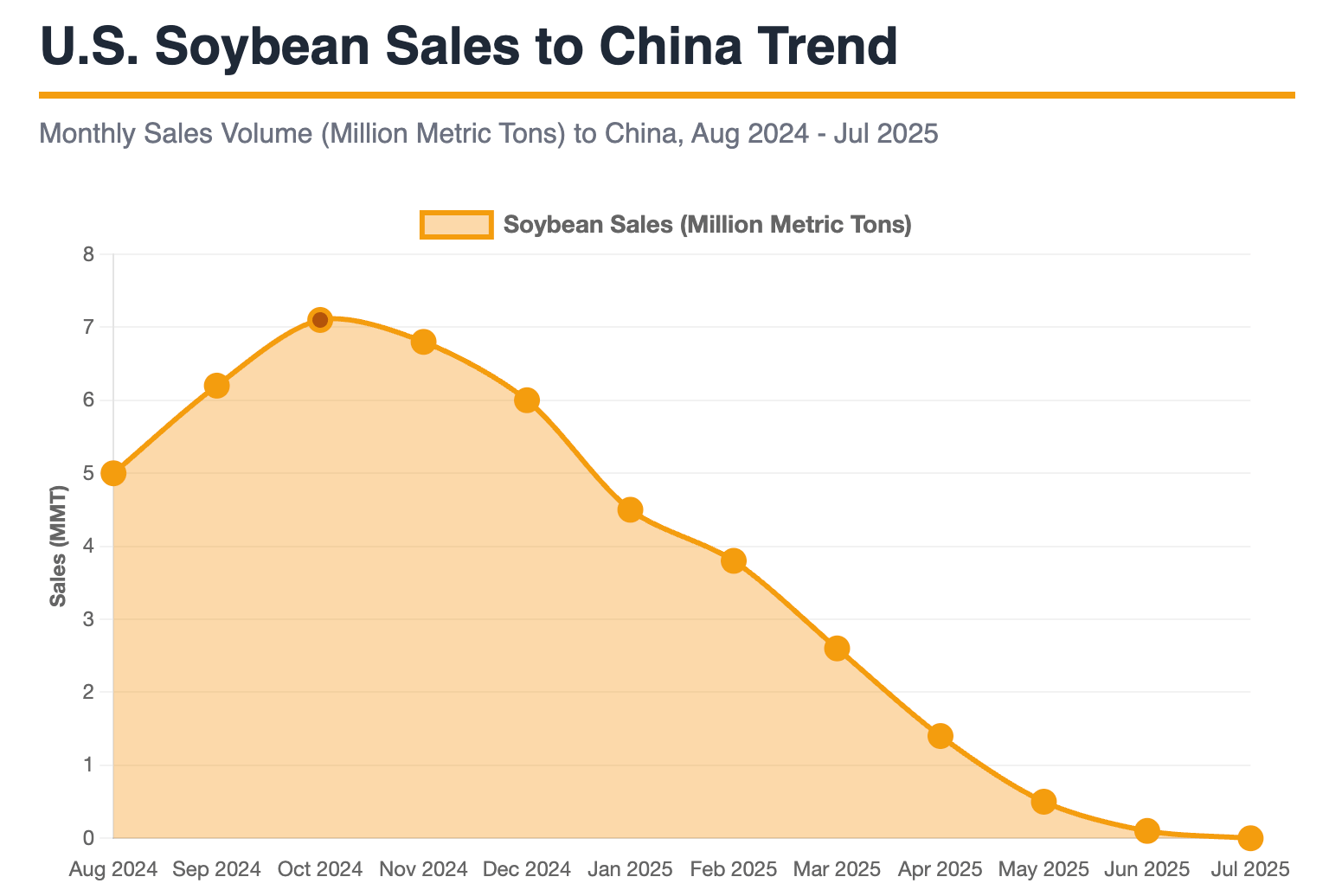

Between January and July 2025, U.S. soybean exports to China fell 39% by volume, dropping to just 5.9 million metric tons, according to government trade data.

What’s worse, it has not made a single booking in September. For context, China typically secures around 40% of its annual U.S. soybean needs by early October. This year, that window has come and gone with virtually no new purchases.

Overall, U.S. soybean exports are down 23% year-over-year, and in its latest outlook, the USDA projects total shipments at 46.4 million tons for 2025/26, down from 51 million tons the previous year.

“This is a five-alarm fire for our industry,” said Caleb Ragland, president of the ASA, in an interview with the Associated Press.

On October 15, President Donald Trump called China’s refusal to buy any U.S. soybeans an “economically hostile act,” in a post on Truth Social.

So where is China getting its soybeans now? That’s where Brazil — and more recently, Argentina — have stepped in.

Battle of America

For years, China was the largest buyer of U.S. soybeans, but the reverse was never true. Beijing has spent more than a decade quietly diversifying away from American supply, substituting it with South American producers, particularly Brazil.

For instance, between 2016 and 2024, the U.S. share of China’s soybean imports fell from 40% to just 18%, according to the USDA. On the other hand, in the same period, Brazil’s share jumped by roughly 57%. In fact, in 2024, China imported 71% of its soybeans from Brazil.

And the trend continues.

Between January and August 2025, China imported 73.31 million metric tons of soybeans, with Brazil supplying roughly 72% of that total, according to data from the General Administration of Customs. In September, China’s soybean imports surged to 12.87 million metric tons, and Brazil alone accounted for nearly 11 million tons — underscoring how Brazil has replaced the United States as China’s primary supplier.

China’s turn to Brazilian soybeans isn’t just a geopolitical move — it’s also basic economics. Thanks to lower land and seed costs, Brazilian soybeans have long been cheaper than U.S. soybeans. Now, with tariffs making American soy even more expensive, Brazilian soy is having its moment.

The American Soybean Association (ASA) says the total duties on U.S. soybeans bound for China have now climbed to 34%, making American shipments too expensive compared to Brazil’s.

Let’s now take the case of Argentina, the newest player in China’s soybean orbit.

In September, the Argentine President Javier Milei briefly suspended export taxes on soybeans, instantly making their grain cheaper on the global market. The move came just days after the United States extended a $20 billion financial support package to help stabilize Argentina’s economy.

The result? Chinese buyers moved fast, booking multiple cargoes almost immediately — at a time when those same shipments would normally have come from U.S. ports. In September, Argentina’s soybean deliveries to China jumped 91.5% to 1.17 million metric tons.

So, the next big question is: Is there any market that can truly replace China for U.S. soybeans?

The Domino Effect

The short answer is no.

China is the ideal soybean customer — a country with a massive population, rising incomes, and an insatiable appetite for pork and poultry, the two animals that consume the most soy meal. Add to that millions of home cooks who rely on soy oil in their kitchens, and it’s easy to see why China remains the single most important market for U.S. soybeans.

In 2024, the United States exported nearly 27 million metric tons of soybeans to China, compared to just 5 million metric tons to Mexico, its second-largest buyer. No other market even comes close to matching China’s scale or year-round demand. Countries such as Vietnam, Egypt, and Bangladesh have increased their purchases of U.S. soybeans in recent years — but it isn’t enough.

For example, Bangladesh soybean exports crossed 400,000 metric tons recently — a notable increase, but still a fraction of what China used to buy in a single week. Despite rising shipments to Vietnam, Egypt, Thailand, and Malaysia, total U.S. soybean exports were down 8% by volume year-over-year, at 18.9 million tons.

The missing China trade has already started to affect the soybean farmer. On August 19, 2025, the American Soybean Association sent a letter to President Trump, warning that U.S. soybean farmers are “standing at a trade and financial precipice.”

With no new Chinese purchases ahead of harvest, the ASA said farmers face collapsing prices, mounting costs, and an existential threat to the industry.

Final Words

Soybeans are once again at the center of U.S.–China trade talks. When negotiators from both sides meet in Seoul, the soybean export freeze will be one of the first items on the agenda. In his Truth Social post, President Trump stated that he’s set to meet with China’s president in four weeks, with soybeans set to be a major topic of discussion. Parallel to the negotiations, Washington is reportedly preparing another farm aid package, echoing the relief measures from the first trade war.

And if President Trump fails to reach a trade agreement that compels China to resume buying U.S. soybeans, the demand will once again fall short of production, pushing prices even lower. According to experts, it may even drastically affect the US dominance of soybean production in the future.

This newsletter was written by Shyam Gowtham

Thank you for reading. We’ll see you at the next edition!