In William Shakespeare’s famous play Romeo and Juliet, in the iconic balcony scene, Juliet utters the lines: “What’s in a name?”

Juliet could not have imagined that in the world of modern geopolitics, a name is everything.

For example, when Yugoslavia broke apart in 1991, one of its newly formed nations chose to call itself Macedonia. Greece vehemently opposed the name, arguing it appropriated Greek culture — and for decades, the dispute blocked the country’s entry into the EU and NATO. It finally changed its name to the Republic of North Macedonia.

Fast forward to January 20, 2025. U.S. President Donald Trump signed an executive order requiring all federal agencies to officially refer to the Gulf of Mexico — a 500-year-old name — as the Gulf of America to restore American pride.

Recently, another name coined by a Goldman Sachs economist has landed in President Trump’s crosshairs: BRICS, the bloc of emerging economies comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.

In a July Truth Social post, Trump blasted the group’s policies as “anti-American” and an assault on the U.S. dollar. He has already imposed steep tariffs on three members — 50% on imports from Brazil and India, the highest US tariff rate, and 30% on South Africa. He has threatened an additional 10% tariff on any country that aligns with BRICS.

But why does President Trump see the BRICS coalition as a challenge to his America First trade policy?

In this issue of CrossDock, we are breaking down the journey of BRICS – from its formation to its current status, why Trump thinks BRICS is anti-American, and how the recent tariffs have potentially strengthened the coalition.

New Bloc

2001 was one of the darkest years in modern history. The world witnessed the devastating 9/11 attacks, and at the same time, the global economy slid into one of its sharpest downturns, with output slowing and trade shrinking.

According to the World Trade Organization, global GDP growth fell from 4.5% in 2000 to just 1.5% in 2001. World trade, which had expanded by 11% the year before, contracted by 1.5% — its first drop since the early 1980s. Advanced economies were hit hardest: U.S. per capita output declined at an annualized rate of 2.7 percent, and Japan’s fell by 4.2 percent, according to World Bank data.

But not everything was bleak.

In November 2001, Jim O’Neill, then head of Global Economic Research at Goldman Sachs, published a report titled “Building Better Global Economic BRICs.”

He pointed out that at the end of 2000, the combined GDP of Brazil, Russia, India, and China (BRIC) — which he described as emerging market economies — accounted for about 23.3% of world GDP on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis.

Preview of Jim O’Neill’s 2001 Report

In the report, O’Neill argued that these economies had the potential to grow far larger and projected that by 2050, the combined output of the BRIC countries could surpass that of the world’s richest nations. He also suggested that major global governance bodies, such as the G7, should be restructured to give them a seat at the table.

But what O’Neill did not foresee — nor did any Western power — was that these countries would go on to build a bloc of their own. And, in a twist, they chose to rally under the very name he had given them.

Five years after the report’s publication, in 2006, the leaders of the BRIC countries came together to form an informal group to coordinate on shared economic and political goals.

But this brings us to a central question: why was BRICS formed?

What united them was not a single ideology but a shared identity as fast-growing economies outside the Western fold. And the sense of exclusion they faced on the global stage.

For example, the world’s key financial institutions — the IMF, the World Bank, and the WTO — are dominated by Western powers, particularly the United States and Europe. These institutions often dictate the terms of development lending and trade, while offering little voice to the emerging economies.

Additionally, apart from the United Nations and G20, there was no major forum where emerging economies could discuss their own economic and geopolitical agendas.

And the catalyst that finally made it happen was the 2008 global recession, which hit the West hard but left the BRIC economies relatively stronger, giving them the confidence to come together as a bloc.

In 2009, they held their first BRIC Summit in Yekaterinburg, Russia, where they declared their intention to change the global financial and economic infrastructure, calling for a system that gave greater weight to emerging economies.

But most importantly, they hinted at a desire to reduce reliance on the U.S. dollar, calling for a "stable, predictable and more diversified international monetary system."Just a year later, in 2010, South Africa—Africa’s biggest economy—was invited to join, expanding the coalition into BRICS and cementing its ambition to be a counterweight to the West.

Brick by Brick

Since its inception, the BRICS has been criticized for being a symbolic organization with no real actions to its credit. But that changed in 2014. At their Fortaleza summit in Brazil, the bloc rolled out its first real institutions — a sign it wanted to move from talk to action.

The centerpiece was the New Development Bank (NDB). With an authorized capital of $100 billion, it was billed as a counterweight to the World Bank and IMF, institutions long criticized for being dominated by the U.S. and Europe.

Each member pledged an equal $10 billion to get it off the ground, ensuring no single country could monopolize control.

According to its 2023 annual report, the NDB has approved 105 projects worth $34.8 billion since its inception. Clean energy and energy efficiency dominate the portfolio, accounting for 37% of funding, followed closely by transport infrastructure at 28%.

In 2023, the bank approved nine new projects worth $2.1 billion — nearly two-thirds of which were directed at transport. One of the significant projects that NDB is bankrolling is the Xinjiang Alashankou Port Infrastructure Development Project in China, a strategic upgrade of rail, road, and warehousing at one of the country’s most important inland gateways to Kazakhstan and Central Asia.

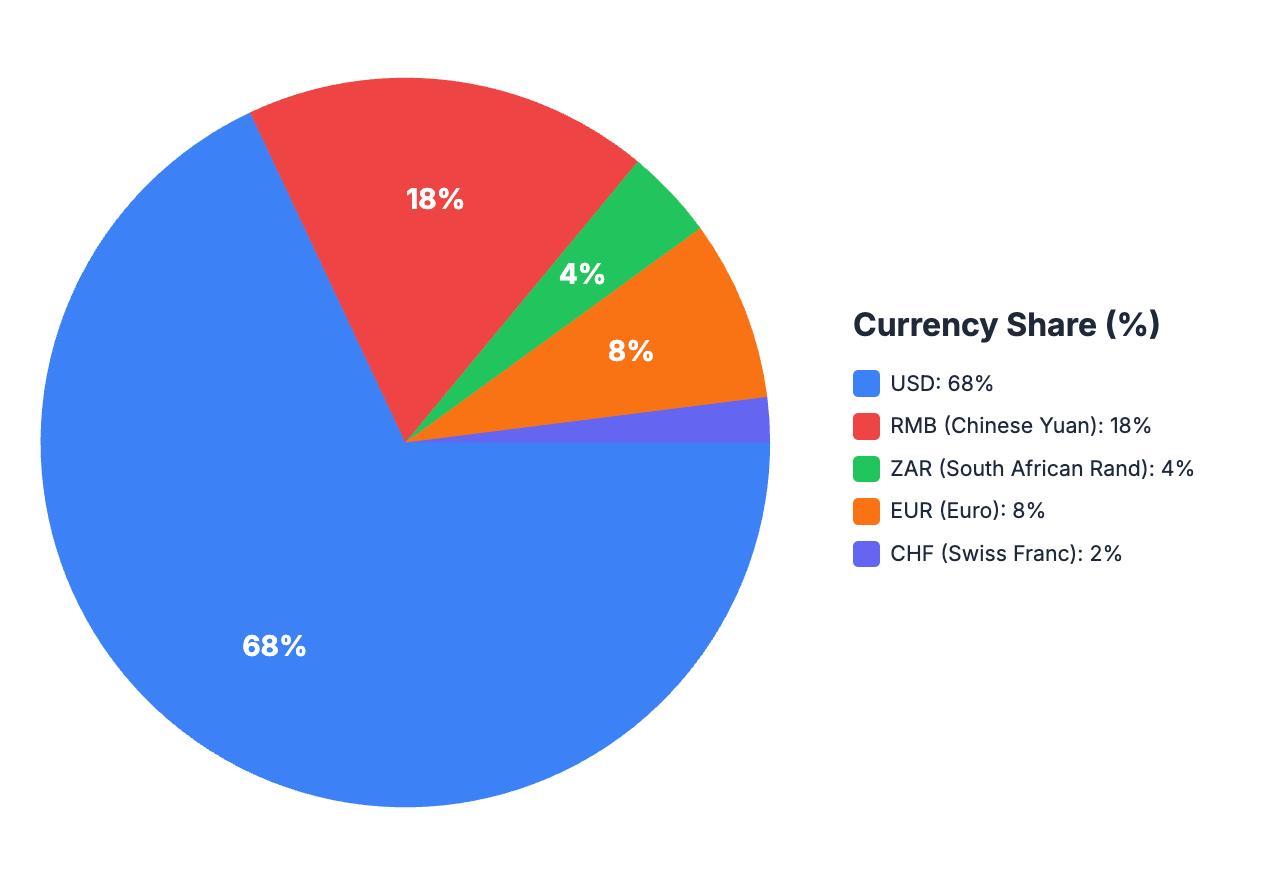

Currency Lending Breakdown of the New Development Bank as of 2022

Similar lendings can be found across the bloc: in India, metro rail systems in Mumbai and Delhi funded by the NDB unclog cities that are also export arteries; in Brazil, road modernization trims transport times for soy and iron ore shipments.

What these projects display is the BRICS’s strategy: not just growth for growth’s sake, but a deliberate push to re-orient supply chains and increase trade flow among BRICS countries.

Interestingly, the lucrative nature of NDB lies not only in what it builds, but in how it lends. Unlike the IMF and World Bank, where funds often arrive with strict austerity conditions, BRICS financing has fewer political strings attached.

This difference has made the bank increasingly attractive to countries caught in the squeeze of debt and development needs. It explains why new members have gravitated toward the bloc: Bangladesh joined in 2021, followed by the United Arab Emirates and Uruguay; Egypt signed on in 2023; Algeria in 2024; Colombia in 2025; and most recently, Uzbekistan.

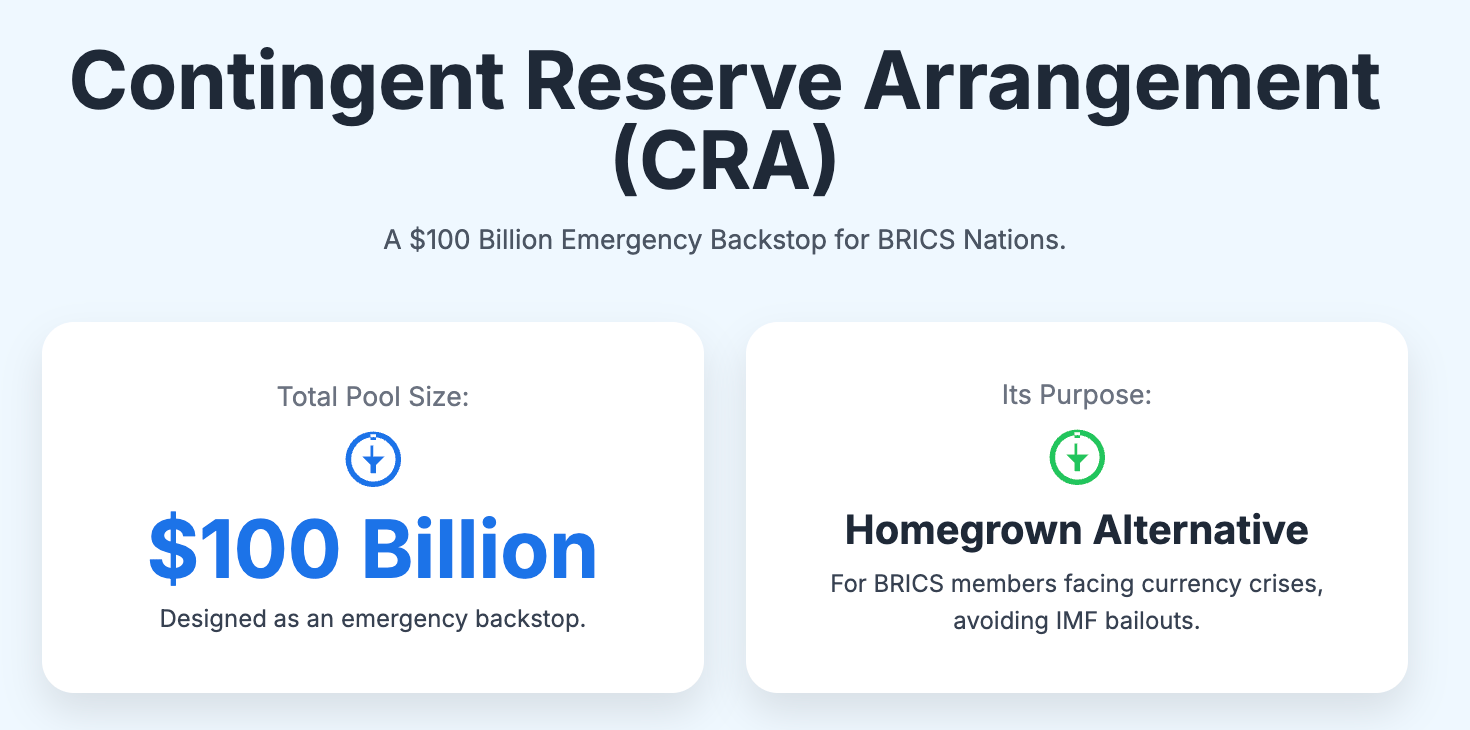

Alongside the NDB came the Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA), another $100 billion pool, designed as an emergency backstop. If a BRICS member found itself in a currency crisis — the kind of event that usually drives countries to Washington for IMF bailouts — the CRA offered a homegrown alternative.

China put in the largest share, $41 billion, while Brazil, Russia, and India each contributed $18 billion, and South Africa $5 billion. Since its inception, no member has claimed the money.

As of 2025, BRICS has grown into a bloc of eleven full members: Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Ethiopia, Indonesia, and Iran. This expanded formation is now referred to as BRICS+.

The bloc now represents nearly 45% of the world’s population and generates over 35% of global GDP on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis.

Interestingly, it is not just about population and GDP — it also sits atop a commanding share of the world’s strategic resources.

The bloc collectively holds around 72% of global reserves of rare earth minerals, a critical input for everything from smartphones to fighter jets. It accounts for 43.6% of global oil production and 36% of natural gas output, according to the International Energy Agency. And in coal, the backbone of industrial power generation for much of the developing world, BRICS+ countries dominate with 78.2% of global production.

It might look like BRICS has everything figured out, but the reality is far from that. Let’s break it down for you.

What’s wrong with BRICS?

While the BRICS bloc has grown in economic and geopolitical stature, it faces significant internal challenges, particularly concerning trade. The most prominent issue is the asymmetrical nature of intra-BRICS trade, where China serves as a dominant hub.

That is because China is the largest trading partner for most of the other members, while their trade with each other is relatively low. This creates a "hub-and-spoke" model rather than a balanced, multilateral network. Furthermore, much of this trade is in primary goods, with countries like Brazil and Russia exporting raw materials and energy to China in exchange for manufactured goods.

This structure perpetuates a traditional, less equitable trade pattern that works against the group's stated goal of creating a new, fairer economic order. Let’s take the example of India, where the country’s imports from BRICS countries totaled $304 billion, while its exports stood at a relatively modest $95 billion, resulting in a trade deficit of $209 billion.

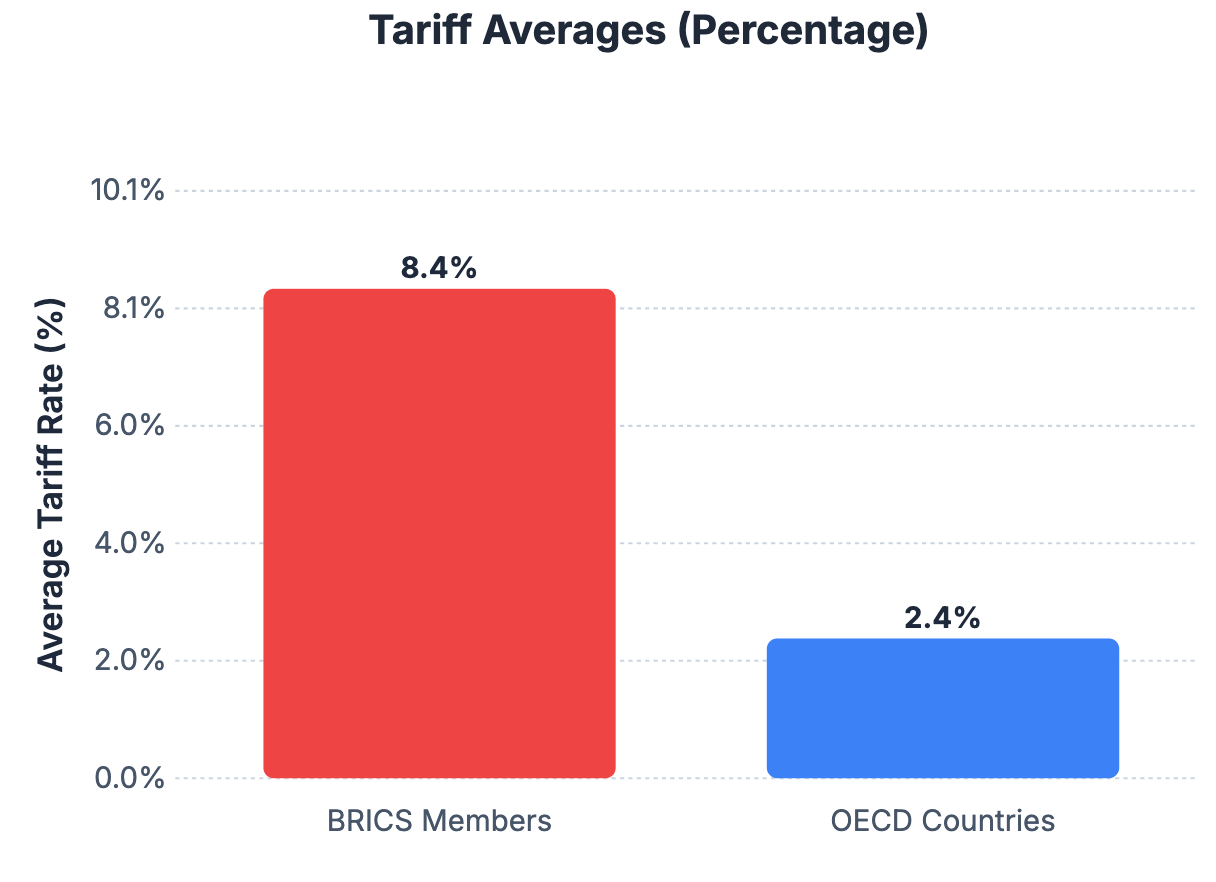

The next important issue is the lack of a formal free trade agreement, which further complicates intra-BRICS trade and makes it expensive. Unlike other blocs like the European Union or OECD, BRICS members must navigate different tariffs, customs procedures, and regulations, which increases transaction costs and hinders trade.

For example, average tariff rates among BRICS members sit at 8.4%, according to World Bank data — almost three times higher than the 2.4% average across OECD countries.

Average Tariffs Between BRICS Members VS OECD Countries

Finally, internal geopolitical rivalries, such as the border disputes between India and China, the Nile dam dispute between Ethiopia and Egypt, also add an additional layer of distrust and competition that can undermine efforts to forge a cohesive trade and economic policy.

Despite these challenges, trade among the five original BRICS nations has been gaining momentum. Between 2021 and 2024, intra-BRICS commerce surged by 40% to $740 billion annually, according to IMF data.

Now there’s one more interest shift happening in BRICS. For years, critics said the bloc lacked a common ideology, but that seems to be changing now thanks to Trump and his tariffs.

United By Tariffs

Donald Trump has never been comfortable with BRICS. In December 2024, Trump threatened 100% tariffs on all BRICS members, calling the bloc “anti-American.” Two months later, in February 2025, he declared on Truth Social that “BRICS is dead.” And yet, in July 2025, as the bloc gathered for its sixth summit, he announced a new 10% blanket tariff on countries aligning with BRICS.

But why does he hate the BRICS? He thinks the BRICS is trying to undermine the dollar’s dominance.

“You have this little group called BRICS. It's fading out fast, but BRICS is; they wanted to try and take over the dollar, the dominance of the dollar, and the standard of the dollar. No, we're not going to let the dollar slide,”

And he’s mostly right.

BRICS has certainly tested those waters since its formation. For instance, Brazil has long been one of the loudest voices calling for an alternative payment system that frees developing countries from dependence on the dollar. In 2023, President Lula da Silva floated the idea of a “BRICS currency” for trade settlement, arguing it would shield members from U.S. sanctions and financial shocks.

China has pushed this idea even harder, expanding yuan-based trade with Russia, settling oil purchases in renminbi, and lobbying for its cross-border payment networks called China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System. In 2024, CIPS processed RMB 175.49 trillion in cross-border Yuan payments — a massive 42.6% jump from the previous year, according to China’s 2024 Payment System Report.

The New Development Bank (NDB), once reliant on dollar funding, has increasingly shifted to local currency lending. By 2023, over 20% of its loans were denominated in currencies like the yuan, rand, and rupee, a deliberate step to reduce reliance on U.S. capital markets.

“I don’t see concrete evidence of an imminent decline in the dollar’s status as the world’s primary reserve currency. But the rise of initiatives to expand trade in local currencies is undeniable, and I see that as a positive development,” said NDB President Dilma Rousseff in the recently concluded 10th annual meeting of the bank.

Interestingly, India consistently downplayed talk of a new BRICS currency, with officials stressing the bloc is not seeking to “replace the dollar” but merely diversify settlement options. Yet quietly, India has been planting seeds of its own.

India and Brazil are exploring a collaboration between their digital payment systems. This collaboration between India’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI) and Brazil’s PIX digital payment system can create a seamless cross-border network. The move would allow faster, cheaper trade and retail payments between the two BRICS economies — without relying on the U.S. dollar.

So, you might ask, have Trump's tariffs affected the BRICS aspirations?

But Trump’s pressure has potentially done what years of summits failed to achieve: it has pushed BRICS nations closer together and increased solidarity between them.

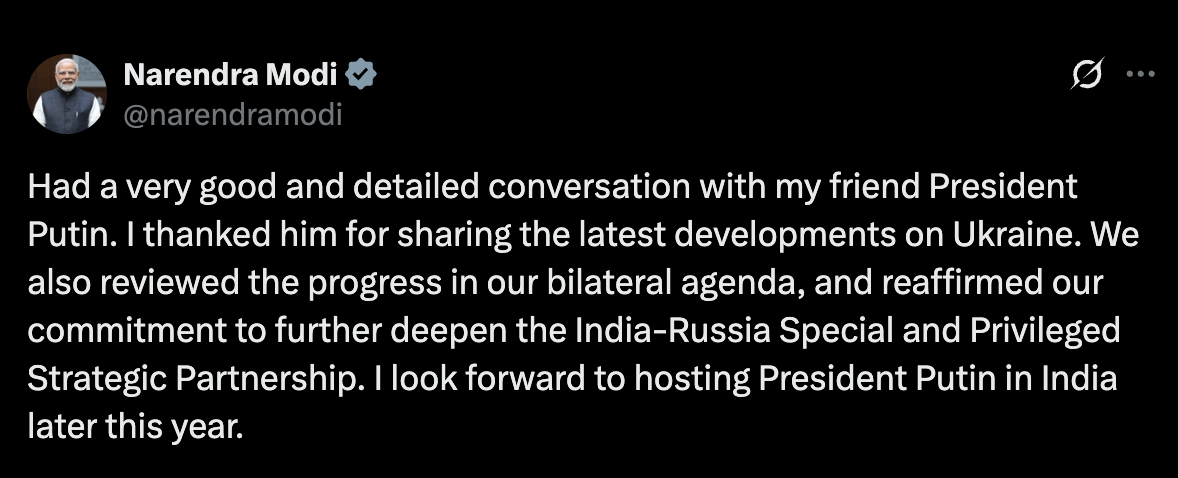

For example, when Washington slapped a 50% tariff on Indian exports, Prime Minister Narendra Modi quickly spoke with Vladimir Putin and reiterated their “special friendship,” amplifying the message on social media.

Indian Prime Minister on X

New Delhi, once wary of Beijing, is now extending a friendly arm: Modi is set to attend the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in China — his first visit in nearly a decade. And discussions have opened on easing trade restrictions, including China’s potential lifting of its export ban on rare earths to India. Putin, too, is scheduled to visit New Delhi later this year, underscoring the renewed alignment.

The 50% tariffs have further strengthened the trade relationship between Brazil and China, boosting agricultural exports and welcoming a fresh wave of Chinese investment projects, from renewable energy to port infrastructure. South Africa, under pressure from U.S. tariffs, has become more vocal about using the New Development Bank to fund infrastructure without dollar dependency.

Final Words

Trump’s tariffs were meant to break BRICS apart. Instead, they have pulled the bloc closer together. Countries like Brazil, India, and South Africa — all seen in Washington as partners — are now finding more common ground with Russia and China.

That creates a real problem for the U.S. For years, Washington has worked to bring India into its orbit, positioning it as a key hub for manufacturing and supply chains moving out of China. South Africa could be a natural partner, too, especially as the U.S. looks for reliable sources of critical minerals at a time when China has shown it is willing to weaponize them. Even Brazil, long considered a friendly player in the Americas, is now leaning further toward China as tariffs bite.

Currently, it appears that BRICS is the only global forum capable of standing up to Trump’s tariffs.

This newsletter was written by Shyam Gowtham

Thank you for reading. We’ll see you at the next edition!