There is a red tunnel in New York City.

Located at 600 Broadway, it is part of Target’s newly revamped SoHo store, which opened on December 9, 2025. The tunnel welcomes customers into the store, but it is more than an entrance. It does not simply lead people inside — it prepares them.

On either side of the passage, the tunnel is lined with carefully curated merchandise: chic apparel, trend-forward handbags, thoughtfully selected scented candles, and other trendy stuff that you can find only in a Target store. Walking through it feels like stepping inside the brand itself.

The effect is intentional, bringing style and design — two things Target has increasingly leaned into for its success over the years — to the forefront before the shopping even begins.

But Target’s SoHo store did not always look like this.

For years, it carried no apparel, positioned mainly as a quick stop for essentials — snacks, beauty products, and everyday basics. Shoppers dropped in, grabbed what they needed, and moved on.

But Target flipped the script.

The revamped SoHo store is part of a broader strategy to reverse the retailer’s declining performance — and Target needs one. The retailer has been stuck in a different tunnel. It has reported consecutive quarters of comparable sales declines, and its shares have fallen roughly 60% from their 2021 peak.

In this issue of CrossDock, we explore Target's turnaround strategy — from appointing a new CEO, and reworking its fulfillment model, to trying to reclaim its reputation as a style destination. We unpack the retailer's latest moves to regain its footing in American retail, with perspectives from the company's leadership.

But before we get to the turnaround plan, we need to understand the events that led to this moment. Let's travel back nearly a decade to 2014, when Target faced a similar situation and hired a new CEO to fix it.

Déjà vu

It was December 2013, and retailers across America were deep into their busiest season of the year. Holiday shopping was in full swing — the make-or-break period that can define a retailer's fortune for the entire year. And Target was no exception. With stores packed and foot traffic increasing, the retailer was hoping for a good run.

But unnoticed, something had gone terribly wrong.

In late November, hackers had quietly infiltrated Target's network through a third-party vendor. For weeks, they lurked undetected, installing malware on the company's point-of-sale systems. Then, between November 27 and December 15 — right in the middle of the holiday rush — they struck.

The data breach was massive, and the largest Target had ever faced. The company first disclosed that 40 million credit and debit card accounts had been compromised. Weeks later, in January, Target’s press release revealed the breach was even worse: as many as 70 million people may have had personal information stolen — names, addresses, phone numbers, and email addresses.

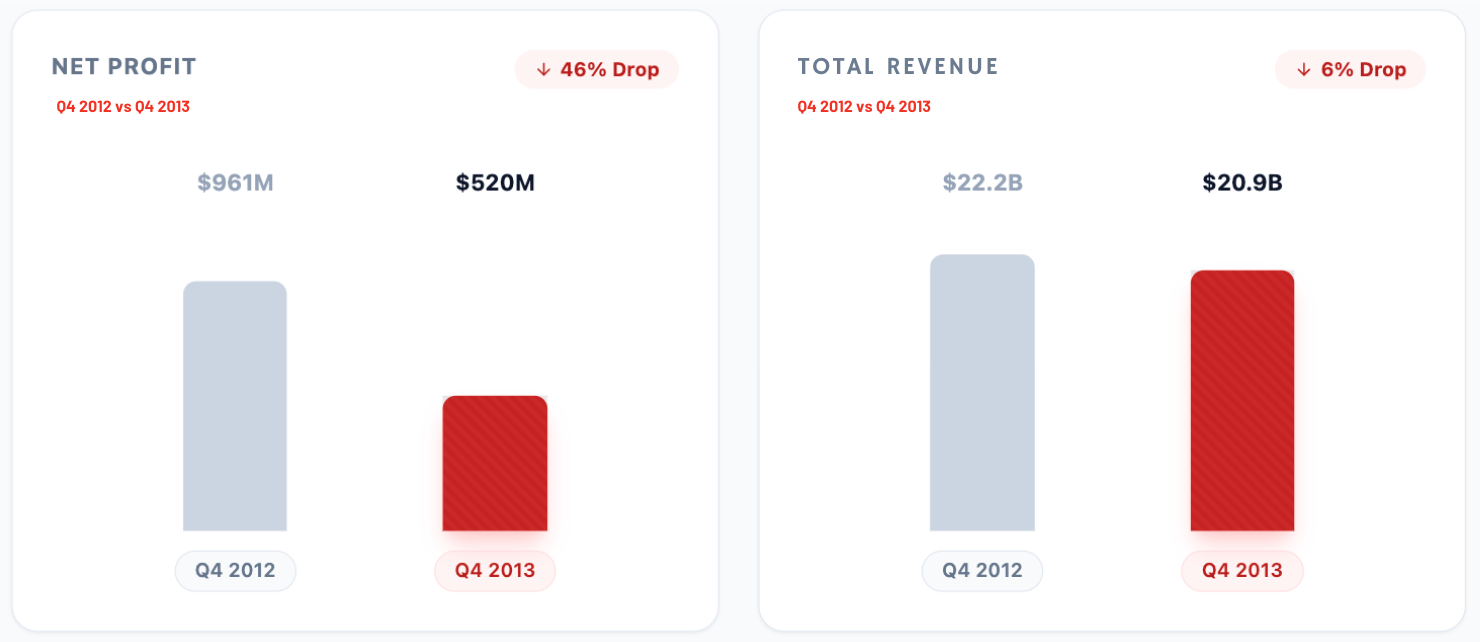

The impact was immediate. By February, in its Q4 2013 earnings report, the retailer reported that profits had nearly halved from a year earlier to $520 million, and revenue had fallen nearly 6% to $20.9 billion. The company said the hack had cost it $61 million — costs to contain the breach, credit monitoring, legal services, fraud losses, and card replacements.

It was not just sales that Target lost. Customer trust was also in shambles. Only 33% of U.S. households shopped at Target in January 2014 — a 22% drop from the same time the previous year, according to a survey by Kantar Retail. Customer traffic had hit its lowest point in three years.

Five months after the data breach, then-CEO Gregg Steinhafel, a 35-year Target veteran, resigned.

But the data breach was not Target's only problem.

While the company was still reeling from the hack, another crisis was unfolding north of the border. Target had rushed into Canada in 2013, opening 133 stores in just over a year. The expansion was a disaster from the start — poor real estate decisions, supply chain failures, inventory issues, and prices higher than customers expected.

To resolve its issues, Target needed both new plans and fresh thinking. So in August 2014, the company did something it had never done before: it hired an outsider.

Upgrade to Continue Reading

Become a paid subscriber of CrossDock to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

Upgrade