Enjoy reading our weekly CrossDock deep dives? Don’t keep us a secret!

Share CrossDock with your friends and network.

Get your brand in front of top supply chain leaders from Amazon, DHL, Walmart, PepsiCo, and more - Advertise with CrossDock.

What do the American Civil War, a nursery rhyme, and a turkey have in common?

On the surface, they seem like three completely unrelated things. But if you know your history, you'll see that they all lead to one of the most important festivals in the United States: Thanksgiving Day.

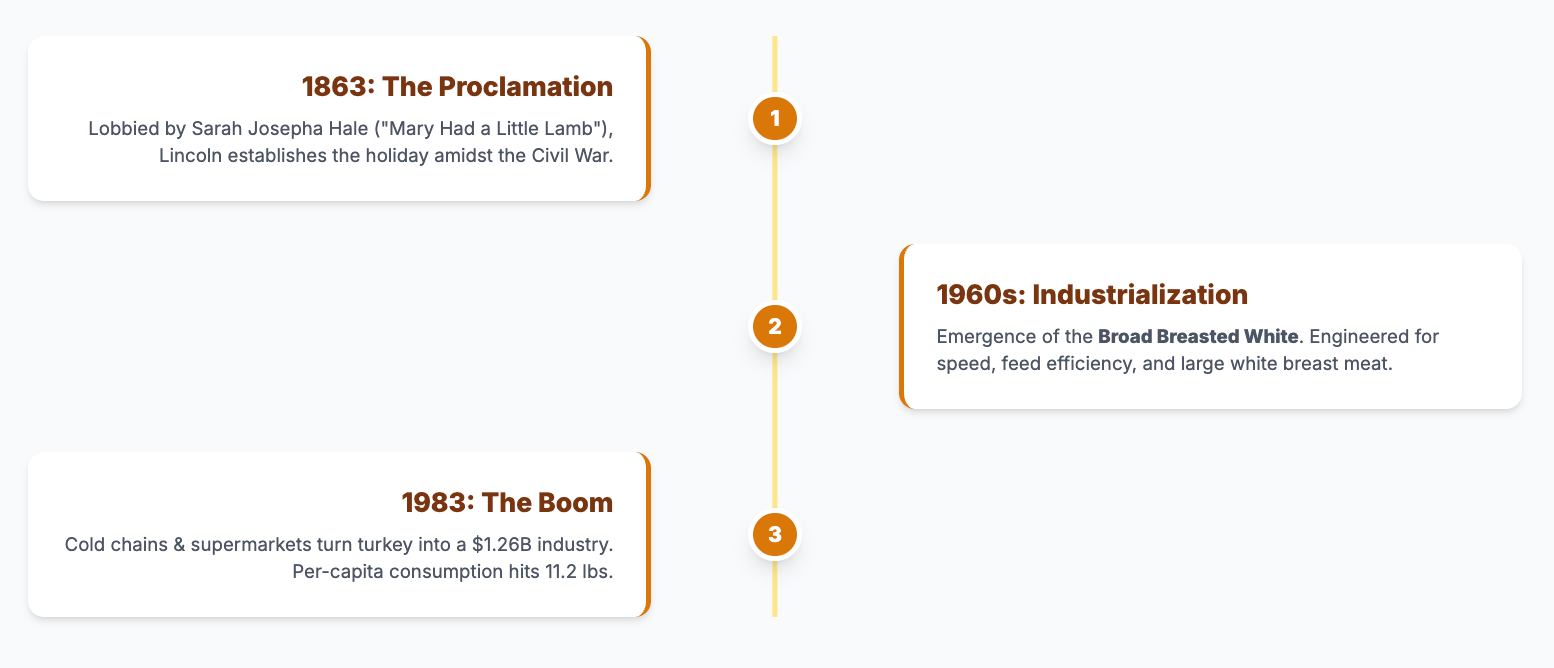

Sarah Josepha Hale, the author of “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” spent nearly three decades lobbying U.S. presidents to establish a national day of gratitude. President Abraham Lincoln finally agreed in 1863, right in the middle of the Civil War, to proclaim the fourth Thursday of November a national holiday.

But how did Turkey end up being the centerpiece of this beloved holiday?

Hale was also partly behind this, too. In her editorials and novels, she repeatedly described Thanksgiving as a harvest feast with a roasted turkey at the center of the table. Also, Turkeys were abundant, large enough to feed large families, and were a distinctly American bird.

Nearly 160 years after the proclamation, today, Thanksgiving Day remains the largest eating event in the U.S., and at the center of it all sits the good ole turkey — with Americans consuming about 46 million birds on Thanksgiving Day alone.

This year, that bird could cost more and raise your Thanksgiving expenses.

According to the USDA, wholesale turkey prices are up roughly 40% from last year. One of the steepest price jumps in recent years — in fact, turkey prices are now more than 80% higher than they were in 2018.

In this issue of CrossDock, we break down the reasons behind the fierce rise in turkey prices and the supply chain behind the sticker shock.

But, to understand all this, we need to know America’s love affair with Turkeys — so let’s begin there.

Tale of a Bird

Turkeys were among the earliest animals domesticated in North America — raised by Indigenous communities long before European settlement. They became so woven into American culture that Benjamin Franklin reportedly wanted the turkey to be the national bird, calling it a “respectable creature.”

Interestingly, up until the 20th century, turkeys in the U.S. were not an industrial product. They were raised on small farms, homesteads, and backyards, mostly free-range and fattened only seasonally.

It was only in the 1950s that the true era of industrialization in American turkey production began. Purpose-built turkey farms replaced backyard flocks, and a wave of new technologies reshaped the industry.

The most important inflection point for the U.S. turkey industry came in the 1960s, when the Broad Breasted White emerged and reshaped the bird into a modern commercial product.

Bred through intensive selective genetics programs, the Broad Breasted White was engineered to grow rapidly, convert feed with remarkable efficiency, and deliver the large, mild-flavored white breast meat Americans increasingly wanted — turning it into the ideal bird for the modern supermarket era.

How America Fell in Love with the Turkey

The next major turning point came with the rise of the cold chain and national supermarket distribution in the 1970s–1980s. Refrigerated trucks, expanded cold-storage facilities, and year-round supermarket demand transformed turkey from a seasonal product into an everyday protein.

Frozen processing allowed birds to be shipped coast-to-coast, stored for months, and sold at scale, while supermarkets used turkeys during holidays to pull shoppers in.

According to the USDA’s Economic Research Service, what began as a modest $270 million enterprise in 1950 had exploded into a $1.26 billion industry by 1983. New technologies — from improved breeding to cold-chain expansion — drove down retail prices, while aggressive marketing shifted turkey from a once-a-year holiday bird to an everyday protein.

The end result: Annual per-capita consumption surged to 11.2 pounds in 1983, up from 8 pounds in 1970 and 6.1 pounds in 1960.

By 2014, the number of turkeys raised in the United States reached nearly 250 million, and the value of production reached approximately $5 billion, according to the USDA.

But a disaster was literally flying in the air toward the United States — ready to wreak havoc on the turkey industry in 2015, and again nearly a decade later.

Deadly Disease

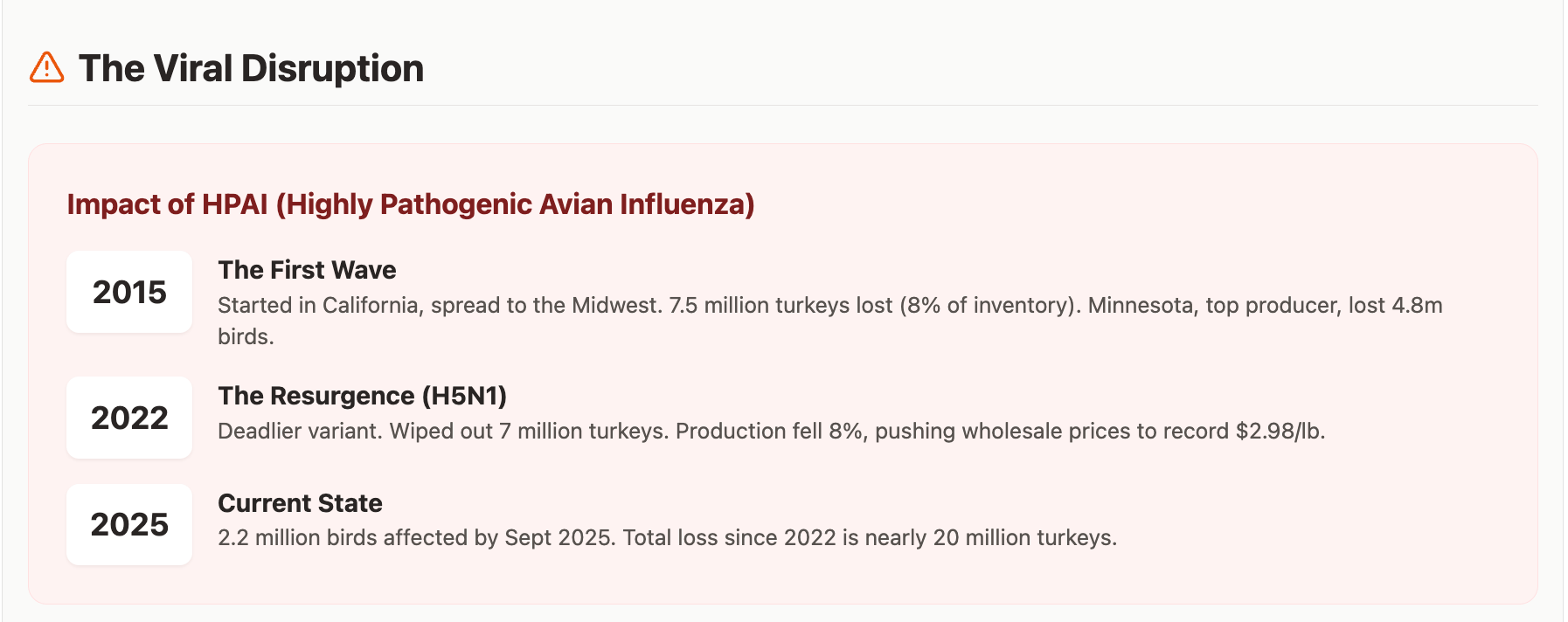

The 2015 avian flu disaster began quietly and almost unnoticed on a turkey farm in Stanislaus County, California, in January 2015. State veterinarians confirmed that a flock there had tested positive for a highly pathogenic strain of avian influenza — the first commercial detection in what would become the worst poultry disease outbreak in U.S. history.

Sadly, the virus didn’t just stay in California. By early March, the first major commercial outbreak exploded in Minnesota. Within weeks, the virus reached Iowa, South Dakota, North Dakota, and Wisconsin, tearing through every major turkey-growing region in the country.

By the time the outbreak finally ended, 7.5 million turkeys were dead or depopulated — roughly 8% of the entire U.S. turkey inventory at the time. The impact was brutally high in the Upper Midwest, the core of America’s turkey belt. Minnesota, the nation’s top producer, absorbed the worst of it, accounting for nearly 66% of all infected commercial turkeys — about 4.8 million birds lost in one state alone.

But it did not end here.

The virus resurfaced again — this time a different variant, H5N1 — and far deadlier for commercial poultry. The H5N1 outbreak wiped out more than 7 million turkeys in 2022, and U.S. turkey production fell by roughly 8% year-over-year, pushing wholesale frozen turkey prices to a record $2.98 per pound just weeks before Thanksgiving.

They say history repeats itself — and in the turkey industry, it turns out viruses do too.

In 2025, the U.S. turkey industry was hit hard once again, with roughly 2.2 million birds affected by Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza by September. What’s worse, the Animal Welfare Institute reports that from February 2022 through June 2025, nearly 20 million turkeys have been killed nationwide due to HPAI — a staggering multi-year loss.

This sustained pressure has pushed the national flock to its smallest size in 40 years. With only about 195 million turkeys left in production — roughly 3% fewer than last year — growers are now operating in one of the tightest supply environments the industry has faced in decades.

This tighter supply has translated into upward pressure on prices.

Wholesale turkey prices are averaging around $1.32 per pound, nearly 40% higher than last year’s $0.94.

A Purdue University study estimates that the average retail price of turkey will hit about $2.05 per pound this November — roughly 25% higher than last year — putting a 15-pound bird at around $31 for consumers.

However, despite the supply crunch and rising wholesale prices, major retailers have announced lower turkey prices this year. Let’s break down why.

Fowl Play

In his October 2025 speech to the American Business Forum, President Trump touted falling grocery costs, saying Walmart’s standard Thanksgiving meal is now “25% lower than one year ago,” calling it “a big deal.”

And he was right about the Thanksgiving deal.

According to Walmart, its 10-item Thanksgiving basket now costs less than $4 per item — with a Butterball turkey priced at just 97 cents per pound, its lowest level since 2019 for 10–16-pound birds.

Other retailers are also offering such offers with a reduced price on turkey.

For example, Target says its Thanksgiving meal this year — a $20 bundle meant to feed four people — is the cheapest it has ever offered. The deal includes a Good & Gather turkey priced at 79 cents per pound.

Similarly, Aldi’s $40 meal for 10 — about $4 per person — is cheaper than last year and includes a 14-pound turkey. Lidl is pushing even lower prices: its $36 meal for 10 is nearly $10 less than last year, and turkeys are priced at just 25 cents per pound. Costco is selling a full Thanksgiving feast for $42 that feeds eight, while Amazon is offering a seven-item holiday meal kit for $25 that feeds five.

So why are retailers doing this?

At first glance, it makes no sense. Simple economics says retailers shouldn’t slash prices on a product they’re paying more for.

But turkeys aren’t about profit. They’re about traffic.

Retailers deliberately keep turkey prices low — sometimes even below wholesale cost — because turkeys pull shoppers into the store during the biggest food-shopping week of the year.

Today’s shoppers are far more price-sensitive than they were even a few years ago. After three years of elevated inflation and current tariffs, consumers are trading down, switching stores, abandoning brands, and hunting for deals more aggressively.

According to a Numerator study, 82% of consumers say they plan to change their shopping habits in response to tariffs — cutting back on nonessential spending, hunting for sales and coupons, delaying big-ticket purchases, and shifting toward lower-priced retailers or discount chains.

So, most households buy a turkey only once a year, but they buy everything else at the same time: vegetables, butter, rolls, desserts, drinks, snacks, baking items, and holiday extras. That “holiday basket” carries far higher margins than the turkey itself. So even if a store loses a little on each bird, it earns it back on the rest of the cart — and wins customer loyalty during a competitive season.

Let’s take the example of Walmart here. Yes, Walmart’s 2025 basket costs less than last year's, but it has reduced the number of items and changed the product mix.

So, will retail turkey prices be down this year? Not exactly. It all depends on when and where you buy.

For example, the timing of turkey orders by retailers also plays a major role — most supermarkets lock in their holiday purchases months in advance, meaning they’re often selling birds bought at earlier, lower wholesale prices even when current market prices spike.

“Retailers that didn’t secure their turkey orders early may face steep spot-market prices, which could impact availability and cost,” said Dr. Michael Swanson, chief agricultural economist at the Wells Fargo Agri-Food Institute, in an interview with CNBC.

In short, customers could pay anywhere between $15 - $20 more for a standard 16-pound turkey if they buy it from a retailer forced to source birds on the spot market rather than one that locked in cheaper wholesale contracts months earlier.

That price also varies by region. The Thanksgiving grocery haul is projected to be the cheapest in the South at $50.01 and the most expensive in the West at $61.75, according to the American Farm Bureau Federation.

Final Outlook

Interestingly, not everything is ‘cold turkey’ this Thanksgiving. According to the Center for Food Demand Analysis & Sustainability and the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the prices of key sides have barely moved in 2025 — dinner rolls are steady at about $2.70–$2.80 per pound, nearly unchanged from 2024, and mashed potatoes are still just over $1.00 per pound.

But, since 2015, whole frozen turkey prices have climbed steadily, rising far faster in recent years. According to USDA data, prices that hovered near 100 cents per pound a decade ago have surged to about 171 cents per pound in 2025 — one of the highest levels on record.

What’s also worth noting is that turkey consumption has actually fallen — from 5.26 billion pounds in 2019 to a projected 4.48 billion pounds in 2025 — yet prices haven’t dropped. Why? Because producers deliberately cut flock sizes to manage costs, and recurring outbreaks of avian influenza keep supply tight

The long-term trend is clear: every major avian-flu shock pushed prices higher, and each time the market recovered, it never returned to its old baseline.

Finally, with the virus still circulating, no commercial vaccine available, and turkey inventories sitting at historic lows, the risk remains very real that history could repeat itself in 2026.

This newsletter was written by Shyam Gowtham